Elizabeth Rose

Todd Gipstein / National Geographic Society / Universal Images Group / Rights Managed / For Education Use Only

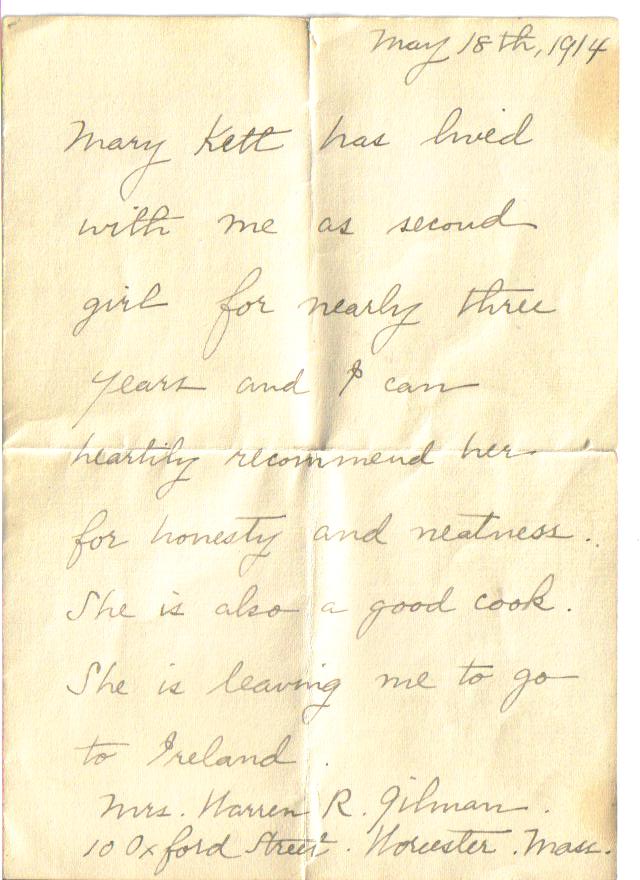

On the first night you brushed your teeth huddled around the blue pila, a large square concrete sink with three chambers. You were a gringo family honoring your oral hygiene despite the absence of running water. The water stored in the central chamber of the pila passed your visual cleanliness test, with the moonlight glancing off its ripples, but you knew that bacterial microbes lurked. No splashing of toothbrushes or cupping your hands to take a swig.

Instead, you shared a few drops of bottled Evian bought at the Atlanta airport by your teenage daughter. When the Evian ran out, your husband used Coca Cola. You were 4,000 miles from home and about to teach English in Guatemala.

As your family brushed you contemplated the pila. The four of you could have climbed into the central storage chamber, becoming immersed to your armpits.

***

Running water was unpredictable in the central highlands where the indigenous Maya live. When the water ran, it was wisely stored in advance of tomorrow’s trickle. The pila was imported by the Spanish who placed the first fountains in a central spot in every town square. As the population grew the people placed private pila in the courtyards of their homes. At that time they had agua pura. Except for centuries of greed, wars, genocide and land grabbing, the water that night in your pila would have had a fighting chance of purity. Nothing in the natural world could have out-competed man at creating such a colossal catastrophe.

***

As you gazed at the southern constellations you missed your usual line-up of Big Dipper, Little Dipper and Orion’s Belt. But you reassured yourself that you could do this homestay with an indigenous family for just two weeks.

You were already an expert at crapping in the outdoors, if need be, and had brought a supply of toilet paper in a giant red suitcase. You had backpacked in Colorado, lived in a Spanish cave, hitchhiked through North Africa, bicycled in China and slept on a haystack in Ireland. You had the resume to qualify and this wouldn’t be insurmountable.

But it would take you days before you noticed the five-gallon blue bottle of agua pura the family stored in full sight in the kitchen. When you noticed you had to laugh, a small rueful laugh at your own blindness. It was a replica of the Belmont Springs bottle from home and yet you had missed it in your summation of objects in the kitchen.

Like a coloring book that asks the child to find everything mismatching in the picture, the sheer number of surprises was mind-spinning. No gas, propane or electric stove, an unplugged empty refrigerator, no spigot of running water and the buzzing cluster of flies congregated around the bowl of breads meant for your breakfast. A glance to the ceiling revealed open electrical wires. This was a kitchen called upon to feed four families, and now yours, three meals a day.

***

You were sad when you first saw your room, smelling of old tortillas and beans. Like a jail cell, no window or closet. No fitted sheets on the bed, no pillows, no bedspread. You wanted to reach your white hand back through time just six hours, before your luggage was packed in the trunk of the Lexus, and open your well-organized linen closet smelling of Tide and grab a fitted set.

In the WC you faced a truth of your visit: Your hosts had never been to a Bed, Bath and Beyond, and why should they need to visit? A single industrial sized nail made a reasonable, though minimalist, toilet roll holder.

***

You quickly got yourself in hand and began to adapt. You learned to bunch up a blanket and spread a towel to simulate a pillow. In the mornings, you drank lukewarm apple tea and ate small round sweet breads selected from the bowl on the table. Kellogg’s Corn Flakes, from giant boxes with the signature red rooster, were consumed with warm powdered milk. Over time, the small green squash, called quiskill, and a chicken bone in your soup became a treat.

You delighted in the bustling streets brimming with smiling people. You liked the dusty switchbacks crisscrossing the green hills between pińon pine, avocado and cedar. You laughed at misshapen trees on every hilltop that reminded you of Dr. Seuss. The hills were spotted with smoke clouds rising from open fires and stoves that reminded you of Little House on the Prairie, but soon you admitted this was another romantic fantasy. The cardboard shacks with aluminum roofs were nothing like log cabins, and the open fires in the living rooms created respiratory illnesses, a leading cause of infections in children and death in the elderly.

You looked into the eyes of the passing women, carrying lumpy mystery bundles on their heads

, and said buenos dias every morning and buenas tardes every afternoon, starting at one minute past noon.

At your lodging you heard 13 people all live underneath one roof without shouting. You saw uncles and aunts hug nieces and nephews, giving kisses just as loving as those given by the mamas and papas. You witnessed joyful reunions between adult siblings every Friday night, following five days of separation because work was in the capital, hours away. You saw the children play in the courtyard, digging with a spoon or flipping a plastic object. Once the littlest girl, just two, pulled down her panties to wee in the dirt. Her five year-old cousin stopped mid-game and, with a gentleman’s flourish, helped her yank her panties up before resuming their play. You witnessed a Saturday morning fiesta-day when 18 women, babies and children crowded into the kitchen and women patted out tortillas while others nursed babies on the floor telling jokes and gossiping.

***

On your return, while laying over in Atlanta, you used the bathroom just to celebrate the toilet paper flushing away. No longer would you have to store it in the little basket with the swinging lid. You ordered a green salad to extol the return of vegetables to your diet. You sat near a white family with three kids, all wearing baseball caps and trendy t-shirts. “Sit there and don’t move,” said the man, as he pulled too hard on the boy’s chair. The boy cried through his meal while no one offered consolation. Like leaving a trance you never knew you had entered, you missed the quiet murmurs redirecting restless children at the dinner table.

At home, you were both relieved and distressed. You had to reconcile a legacy of emotions. You were embarrassed by how tough you found the physical challenges and inconveniences. You were sad that your new friends might never have a vacuum cleaner, hair dryer, hot showers, clothes washer and dryer, coffee pot and a stockpile of food in a working refrigerator, common conveniences in your country. You were guilty of impatience with delayed service in foreign restaurants. You shamed yourself for judgments of the poor. You assigned goodness to the poor everywhere—the ‘halo effect”–creating a kind of noble savage scenario. You knew your lifestyle was thievery, stealing more than your share of worldwide resources, despite your own efforts at recycling and driving a low emissions vehicle.

***

You were happy to reunite with your kitchen with its potable, fluoridated and chlorinated water that flowed any time of day or night, and not just on certain lucky mornings. You filled a glass and drank the cool clean water that tasted like privilege.

Elizabeth Rose is a non-fiction writer based in Massachusetts. She has published in the Boston Globe Magazine, the Newburyport Daily News, Newburyport Magazine, and the Northshore Jewish Journal. She is an MFA candidate in Lesley University’s Creative Non-fiction program. This article is the preface of her book detailing her experiences as a woman of privilege working in Guatemala.

Photo credit: ARLINGTON, VIRGINIA.. Photography. Britannica ImageQuest, Encyclopædia Britannica, 25 May 2016. quest.eb.com/search/137_3166756/1/137_3166756/cite. Accessed 20 Jan 2017.