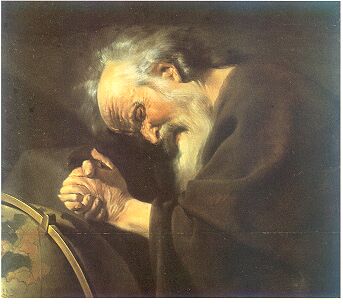

Heraclitus (The Crying Philosoher) / By Johannes Moreelse (after 1602–1634)/Wikimedia Commons

by Joseph Benavidez

The first time I cried as a journalist was driving home after covering a frigid winter event. A month before, a 46-year-old man had gone missing, and his girlfriend, family, and friends were holding a candlelight vigil to draw attention to the case, which had gone cold. The vigil was held on the second floor of a tiny church, and the girlfriend and his sister spoke about the good qualities the man had and how much they missed him.

Being in that church was disconnecting for me. Mentally, I knew a man was missing and probably dead, but emotionally I felt nothing for the man or his family. I interviewed the girlfriend, taking her quotes before effortlessly moving onto the sister and then another attendee. During the moment of silence, I took photos of the small crowd praying. I did my job and left the church happy and proud of myself. I felt like a real journalist and not a college student playing pretend.

But on the drive home it hit me. This guy was dead and no one was ever going to say goodbye to him. In rural Massachusetts, a body can stay hidden in the woods for decades. Without warning, I found myself overwhelmed by a crushing wave of sadness.

Winter on Route 2 means ice, darkness and, if you don’t pay attention, accidents. Everyone who grew up along the highway has a story of teens dying in a car crash; and here I was, alone, crying fat, ugly tears. I forced myself to pull over and rolled down the window to let the cold chill my face. It wasn’t enough and I ended up calling my best friend.

We talked for almost an hour before I calmed down and felt it was safe to drive home.

* * *

To tell the truth, this wasn’t the only time I cried at work. When you’re the primary reporter for an area, you cover everything–fires, natural disasters, deaths, and fundraisers for community members suffering terminal illnesses.

One Tuesday at 6 p.m. a barn caught on fire in Phillipston, the middle of nowhere. I had finished writing my articles for the day and was preparing to head home when the scanner in the newsroom announced the Phillipston Fire Department was requesting backup.

Phillipston is farm country. With fewer than 2,000 residents, it seems there are more cows than people. My editor asked if I would drive out and take a photo. Something for the front page that would grab attention at the newsstand.

I drove the 12 miles to where firefighters from three towns were battling the blaze. The homeowners were not present, but their 27-year-old daughter, who had called 9-1-1, was there.

Before leaving the office, my editor had coached me on how to approach people in such situations

“Be kind,” she’d said. “Ask if it’s okay to take photos. I like to ask if they want some water or something to drink.”

With that advice in mind, I approached the daughter, asked if she needed something to drink, joking that I was finally over 21 so I could legally buy her some vodka.

She laughed. I counted that as a victory. “I don’t know how it started,” she continued, “but the rabbits were still in their cages. I’d just delivered 24 piglets today and now…now they’re gone.”

I couldn’t walk away–these were amazing quotes and my article was going to be 100 times better if I could just get her to cry.

“Did you name them?” It slipped out before I could think about it.

“No, not yet.” She smiled weakly, and I knew she wasn’t going to answer any more questions.

The journalist walks a tight line between asking appropriate questions and being an asshole. I hope I never crossed that line, but I do think I might have picked at people’s wounds a little too soon.

* * *

Another time work gave me emotional whiplash was when Jeremiah Oliver’s body was discovered. The Oliver case gained nationwide notoriety, culminating in the fall of 2014 when the head of the Massachusetts Department of Children and Families resigned in disgrace.

Five-year-old Jeremiah lived with his brother, sister, mother, and his mother’s boyfriend in Fitchburg. His biological father, Jose Oliver, had been arrested on drug possession years earlier and the courts had awarded his mother full custody, marking the family as a case for state check-ins.

In October of 2013, Jeremiah disappeared. A month later, his mother finally reported him missing when a school counselor informed police that she hadn’t seen Jeremiah in a while.

When the word got out that Jeremiah had been missing for over a month before police were notified, news vans raced to Fitchburg to report on the little boy who had been forgotten. Articles and editorials flooded the newspapers. Search parties with cadaver dogs from Connecticut met almost weekly. Churches held prayer vigils. Jeremiah’s biological father was arrested for drug possession again. Anything remotely related to the case made front pages on all the papers.

Fast forward to April 20,14. A suitcase with a boy’s lifeless body inside is found off the highway not far from Jeremiah’s hometown. At the time I was vacationing in Los Angeles. My best friend saw the news and texted me.

I immediately went to the hotel lobby to watch a blonde newscaster on the large-screen TV relay details of the find. It wasn’t confirmed for another week, but everyone knew that Jeremiah had been found.The first story I had ever written as a reporter had come to a close–Jeremiah had been shoved into a suitcase and thrown on the ground as if he was a piece of garbage.

I sat in the lobby stupefied, remembering something one of Jeremiah’s neighbors said when I had interviewed her during the initial search.

“I’ve lived here over six years and I’ve never said hello to him,” she said that snowy morning. “If I couldn’t help him when he was alive, I’ll help him now.”

I couldn’t help Jeremiah when he was alive and now that he was dead, I asked myself, “Did I help him or did I profit from his death?”

I still don’t have an answer for that. I was gleeful when my article and photographs about the search landed on the front page of the paper, buying copies for my mom, my sister, myself, three friends and a former boss, smiling widely when I delivered them.

Some days I feel guilty over that pride, other days I don’t.

I quit being a journalist after two years. Too many heartbreaks, too many late nights. Still, it’s probably the only career where crying at work is a sign of job well done, and I’m not ashamed of those tears.

Joseph Benavidez is an editor for Buck Off Magazine, proud cat daddy and was a sexy Captain America for Halloween. He enjoys taking photos, sleeping until noon, and reading flash fiction. A graduate of Salem State University, he has left journalism and e

mbarked upon a literary career.

As someone whose writing lakes clarity, I admire your writing. Its so simple yet effective and full of emotion.

Thank you! It took about a year to write this and there were many edits.

A year? My goodness! I wrote the memoir right for this and It took me a good month, in which I made 5 reasonably different versions of it, but even then I thought it was excessively slow for writing 1400 words!

I’m an amateur writer, but I think its safe to assume that 1 year is a very long time for 1100 words. What made you decide to take your time with it, if you don’t mind me asking?

No worries! It’s was less taking my time and more writing it in pieces. I wrote the first two-thirds all at once but then didn’t come back to it for months. I was also living it, so for some of that time frame I wasn’t writing but actually experiencing it. There was also a lot more to this at first, but through edits, I deleted chunks that weren’t needed or didn’t add much — such as another barn fire I covered.