by Joseph G. Smeall-Villarroel

If I forget thee, O Jerusalem…

When Allis was three years old and living with his parents in Wisconsin, his great-aunt Meropia came to visit from North Dakota. It was the middle of August, when Catholics remember the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary into heaven, at the end of her mortal life. For the occasion, Tía Meropia brought presents—a gift certificate for ice cream, and a VHS copy of the movie Mary Poppins. On the video cover, Mary Poppins and Bert the Chimney Sweep danced around with a flock of bow-tied penguins.

When Allis was three years old and living with his parents in Wisconsin, his great-aunt Meropia came to visit from North Dakota. It was the middle of August, when Catholics remember the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary into heaven, at the end of her mortal life. For the occasion, Tía Meropia brought presents—a gift certificate for ice cream, and a VHS copy of the movie Mary Poppins. On the video cover, Mary Poppins and Bert the Chimney Sweep danced around with a flock of bow-tied penguins.

The ice cream was delicious but short-lived. The movie, on the other hand, enthralled Allis. It became the extended metaphor that defined his early childhood.

***

Like you, Allis would grow up to become someone who remembered more details from his past than most people do. He remembered Tía Meropia’s gift well, without understanding why. Its significance would become clear years later, after he had met you.

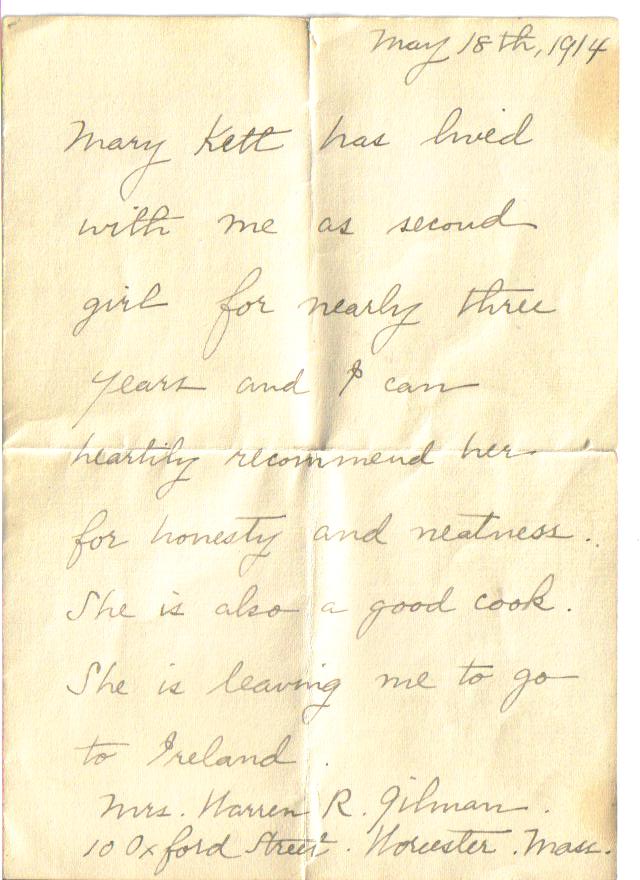

The following year, in Worcester, MA, you sat in the backyard playing with your sister. You were three years old. You both looked for lizards and toads and all sorts of crawly things. Any that you found, you added to your elaborate make-believe games. Your sister was a budding director, and you were only too glad to play the starring roles in her stories.

You had often felt troubled by things that didn’t seem to bother other people, like defining the boundary between imagination and reality. This day, your sister had invented a story in which all the dinosaurs got herded onto a boat that floated above a flood that covered the world. You saw there were storm clouds on one side of the sky. You were used to seeing it rain. The sun was setting on the other side of the sky, between two of Worcester’s seven hills. An arc appeared across the storm clouds—purple inside blue inside green inside yellow inside orange inside red.

These sights gave you such a feeling of looming terror—unfamiliar, overwhelming and magnificent—that you began to cry. You didn’t understand why the sun should shine at the same moment that it rained, nor what had caused the rainbow. Your father ran outside and took you in his arms to comfort you. Then you knew there was nothing to fear.

***

A few years later, your mother began taking you both to the Mendon Zoo on Saturdays. You would look at the animals, and then go to the main pavilion to get ice cream, from a stall shaped like a lion’s head.

The zoo ritual seemed like more of your sister’s make-believe games, although you didn’t fully realize it yet. Your interest in animals had waned since those early days of looking for backyard critters to populate her dramas. Nature did not, it seemed, mean for you to develop much of a connection to animals. But the Blessed Virgin Mary intended to override Nature’s thoughts on the matter, late in May, when you were seven. And she did.

That Saturday was hot. You had just finished your ice cream, when you caught sight of the Royal Penguin exhibit. You had seen the penguins before, but never truly noticed them. Something about the penguins struck your fancy that day, where previously they had seemed indistinguishable from the other animals.

You asked your mother if you could pet the Royal penguins.

She said no, it was against the zoo rules.

You protested that if you could touch and even eat the ice cream, then it stood to reason that you should also be allowed to touch the penguins. To prohibit one but not the other was an unfair double standard.

Your mother replied that the penguins and the ice cream were two entirely different things.

When nobody was looking, you tried to scale the fence at the penguins’ enclosure. The zoo attendant pulled you down. She asked you what you were doing.

You told her your wish to pet the penguins. But like your mother, she said no touching the penguins. That was the zoo rule. You told her about the double standard, but she remained unimpressed. The penguins and the ice cream were two entirely different things.

Your mother came over looking for you. She apologized to the attendant. By this point, you were starting to cry at being thwarted in your efforts to do the one thing you had ever truly desired to do at the zoo. Over the insistent sound of your bawling, the attendant asked your mother if she understood that the penguins and the ice cream were two entirely different things, and requested that she please keep a closer eye on you, because otherwise you might get hurt.

Other kids around you were staring, and their parents were starting to move away quickly, dragging them by the wrists.

You had glimpsed briefly the boundary between where the play-acting ended, and real life began—it was like the eerie silence you hear the split second before a tornado touches the ground. You had crossed the line. You couldn’t go back to ice cream now that you had discovered the superior charms of the Royal penguins. Why didn’t anybody understand that?

For some time, your mother would not take you back to the zoo because of the embarrassing scene you had caused. But she eventually did take you back, right around the middle of August that same year. You ran for the penguin exhibit. But it had disappeared. Then you saw the sign across the front of the empty enclosure—the Royal penguins had been a traveling exhibit.

First you couldn’t touch the penguins, but now you couldn’t even look at them. The one thing you had ever truly wanted to do at the zoo! It was all so unfair. You burst into tears.

Your mother said she was sorry about the Royal penguins. She asked if some ice cream would make you feel better.

***

Many years later, at a college in western Massachusetts, your memory about the Royal penguins and the ice cream found its way into a story you published in the college’s literary magazine. That was the same year you began playing guitar for the campus Catholic mass, under Allis’s direction. He was one grade ahead of you.

Allis read your story. He thought it sounded familiar, without understanding why. Your friendship with him was weird. Sometimes, arguing with Allis, or even just seeing him briefly across a crowded room, he gave you a feeling you also got every now and then, catching sight of your own reflection in the bathroom mirror, where for just a moment, it seemed truly like you were looking at a perfect stranger whose life story—warts and all—you happened to know intimately.

A couple of years after that, you and Allis were sitting at dinner with other people in the college dining hall. You mentioned the earliest memory you had, of how you had cried the first time you saw a rainbow during a cloudburst, and then your father had comforted you. The feeling Allis got from the story about penguins and ice creams returned to him. This time it stayed and grew, despite that (or maybe because) you and he took paths that diverged after college, first gradually, then suddenly.

You both graduated. Some years later, wandering the streets of a faraway city, also built on seven hills, Allis found himself revisiting the memory you had imparted about the rainbow and your father. At times, it replayed in his mind like an infinite loop, against his will. Allis couldn’t understand why he still talked to himself about that memory of your memory. It had been years since you and he had spoken. It felt like your memory had happened to Allis, but he was sure he had never cried about seeing a rainbow, or about penguins and ice cream. He would have remembered things like that. Sometimes he wondered if it was just because of the rainbow’s associations with the indigenous political movement in Bolivia, his mother’s home country. Or maybe it was because rainbows made him think of leprechauns and pots of gold, since he saw you as Irish-American? The rainbow, the penguins, the ice cream, and the crying bedeviled Allis.

***

It was early spring, right before Allis’s nervous breakdown began. He sat in an ice cream parlor in Boston. He had just finished visiting the aquarium with some college friends who were in town. They had seen a display of Royal penguins. Allis’s mind floated back to the eerie feeling of familiarity that you had sometimes given him.

Then he remembered something he hadn’t thought of before.

When Allis was in eighth grade, five years before he first met you, his father took him and his brother on a long road trip from Wisconsin to Oregon to visit his aunt Aretha and her partner. She had been estranged from the family for many years. The trip was a mending of burnt bridges.

Passing from South Dakota into Wyoming, the Black Hills’ jagged forms leveled out. The car entered a wide plain, and stopped at a gas station to refill. Looking back on that trip years later, sitting at the ice cream parlor in Boston, Allis could still remember the wind when they stepped from the car. He would never forget, as long as he lived. He had to push against it—it felt solid—to cross the parking lot into the nearly deserted station. They saw no humans for miles after that. As they drove, the wind howled all around the flimsy vehicle.

The wind gave way to billowing clouds—tenebrous, gray and purple. They gathered across the plain, piling up against the first ridge of the Rocky Mountains that blossomed from the horizon. Allis’s father drove straight towards it. If you had been there at that moment, you too would have heard the sprinkle of rain splattering against the car as it pushed through the wind, like a little yellow bird. The rain turned into a torrent and the wind continued. If you had been there, you would have seen bolts of lightning at the exact spot where they touched the barren ground of the Wyoming high plain, and the sky all around, and the thunder purred and snarled after it. Allis didn’t cry, but deep within himself he felt a looming terror—unfamiliar, overwhelming and magnificent—of what? Maybe that lightning would strike the car, or that the wind would flip it over.

Still they drove. As they neared the western ridge, sunlight streamed out through the thunderhead against the mountains. Looking back over his shoulder, Allis saw three gigantic rainbows inside one another—purple inside blue inside green inside yellow inside orange inside red.

“God is watching us,” his father mused aloud, in a tone of voice that sounded like he was both awake and dreaming. Then Allis knew there was nothing to fear.

***

Sitting at the ice cream parlor in Boston, Allis’s mind floated back over this memory again as he thought again of how your father had once comforted you when you felt frightened by the storm and the rainbow at the age of three. It floated over the exhibit of Royal penguins he had just seen, and the ice cream he was licking slowly now.

He understood better why your childhood memories had haunted him across the coils of space and time that had separated the two of you. Tía Meropia did after all have a knack for giving gifts that turned out to have a weird resonance later on, at a certain distance. Silently he toasted her health and wealth with his ice cream. And the thought also crossed his mind, as he licked the cone: Royal penguins mate for life.

Far and away—at that moment, somewhere in Wyoming, close to the spot where Matthew Shepard died once—you sat alone, watching a rainbow on one side of the sky while the sun set between two mountains on the other. You felt a spring breeze rustle your blue and orange baseball cap, so that it momentarily rose into the air just above your head. The wind whistled around you. It’s such a weird feeling—when your heart remembers something that your mind cannot. You began humming John Coltrane’s cover of “Chim Chim Cheree,” without understanding why.

***

The following winter, after Allis’s nervous breakdown had run its course, he went to the freezer one night, a few days after Christmas. He was at his mother’s house, in Wisconsin. His mother Nadia had forgotten about one of the ice cream drumsticks, out of the ones she had stocked in the freezer, the previous summer. He fished it out from the back of the piled up food items, and ate it when he got sleepy. And then he dreamed he was trying to charm a flock of penguins so they could fly. He’d been shouting esoteric gibberish with amulets and all manner of occult hokum, but to no avail.

Then Allis’s mother came over looking for him, carrying a rainbow-colored umbrella. She asked him what he was doing.

He told her his wish to make the penguins fly.

“Oh Allis,” Nadia said, “why do you always complicate things that are really quite simple. Here:”

She waved her hands once in a graceful motion.

The penguins rose into the air, just above the ground. With a flap of their stubby wings, they barreled high into the sky, far and away, towards one of the seven hills of Worcester. Allis turned over in his sleep. He smiled slightly, without understanding why.

Joseph G. Smeall-Villarroel graduated from Amherst College with a B.A. in English and music in 2010. Since then, his work in fine arts, education and academia has taken him through the cityscapes of Green Bay, WI, the San Francisco Bay Area, and the Massachusetts Bay area. He lives in Newton.

Photo credit: King penguin couple (Aptenodytes patagonicus), Spheniscidae, Neck, north coast of Saunders Island, Falkland or Malvinas Islands (British overseas territory). Photograph. Encyclopædia Britannica ImageQuest. Web. 10 Jun 2016.

http://quest.eb.com/search/126_513788/1/126_513788/cite

Pablo Picasso (1881-1973), Women Running on the Beach, Summer 1922./ De Agostini Picture Library / Universal Images Group / Rights Managed / For Education Use Only

Pablo Picasso (1881-1973), Women Running on the Beach, Summer 1922./ De Agostini Picture Library / Universal Images Group / Rights Managed / For Education Use Only

When Allis was three years old and living with his parents in Wisconsin, his great-aunt Meropia came to visit from North Dakota. It was the middle of August, when Catholics remember the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary into heaven, at the end of her mortal life. For the occasion, Tía Meropia brought presents—a gift certificate for ice cream, and a VHS copy of the movie Mary Poppins. On the video cover, Mary Poppins and Bert the Chimney Sweep danced around with a flock of bow-tied penguins.

When Allis was three years old and living with his parents in Wisconsin, his great-aunt Meropia came to visit from North Dakota. It was the middle of August, when Catholics remember the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary into heaven, at the end of her mortal life. For the occasion, Tía Meropia brought presents—a gift certificate for ice cream, and a VHS copy of the movie Mary Poppins. On the video cover, Mary Poppins and Bert the Chimney Sweep danced around with a flock of bow-tied penguins.