by Edmund Schofield

Editor’s Note: As a rule, we don’t publish work by older, established writers, but we make an exception with this piece by the late Edmund Schofield since it tells the story of an English teacher who had the rare ability both to instruct and inspire. Anna Shaugnessy mentored young writers who went on to great success–Stanley Kunitz, MIlton Meltzer, Charles Olson, and Nicholas Gage. Every young writer should be lucky enough to come across an Anna Shaughnessy.

We learned about this piece through Joan Gage, who featured it in her blog, A Rolling Crone. We are grateful to be able to publish this edited version of the essay in the Journal.

There is a further twist to the tale. Schofield’s original essay described three writers mentored by Miss Shaugnessy, and only at the last minute did he discover that Nicholas Gage, Joan’s husband and an accomplished author whose books include “Eleni,” which was made into a successful movie of the same name, and “A Place For Us,” had also been a student of hers. Gage’s thoughts on his old high school teacher are in a postscript to the essay.

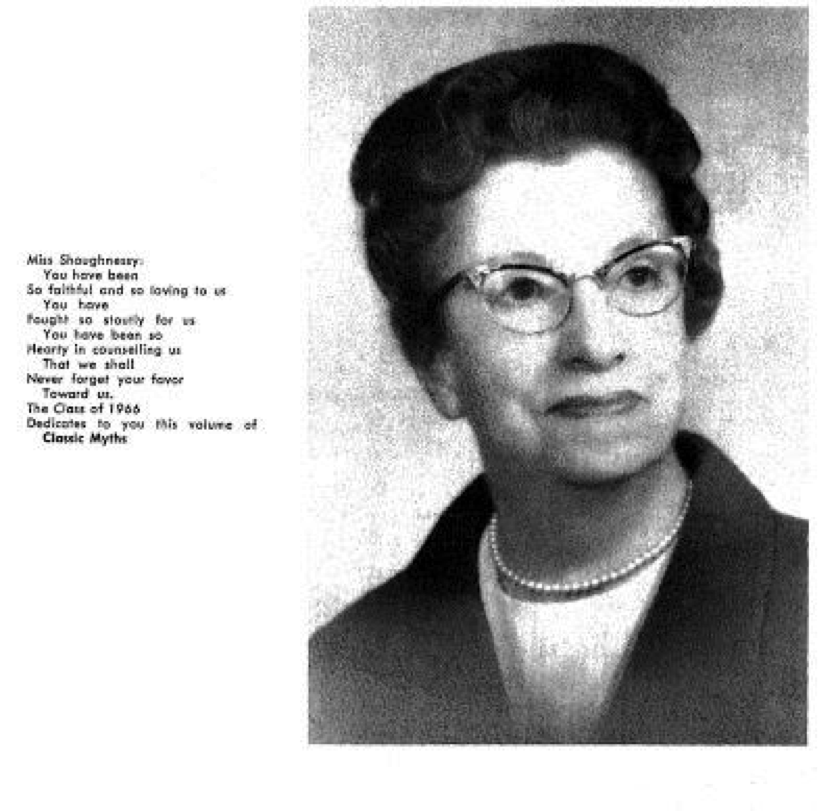

Dedication to Anna C. Shaugnessy from the Classical High School yearbook of 1966.

Edward Tyrrel Channing taught writing at Harvard for 31 years during the early 19th century. Among his students were such renowned authors-to-be as Emerson, Thoreau, Richard Henry Dana, Thomas Wentworth Higginson, Oliver Wendell Holmes, and James Russell Lowell. Quite a haul for one professor!

Yet if Harvard had its Edward Channing, Classical High School in Worcester, Massachusetts, had its Anna C. Shaughnessy. And if Channing had his Emerson, Thoreau, Dana, Higginson, Holmes, and Lowell to brag about, Anna Shaughnessy could boast that she had fledged her very own brood of aspiring writers.

She was born in Cherry Valley in 1896 and died in 1985 at Clark Manor Nursing Home in Worcester—the two places scarcely two and a half miles apart. A devout Catholic, she received many honors from her Church, including the Pro Deo et Juventute Award (“for God and Youth”) from the Diocese of Worcester.

Her father, Michael, was born in Ireland and worked as superintendent of a woolen mill in Cherry Valley. Her mother, Anne (Daly), was born in Pittsfield. The family of twelve moved into Worcester early in the twentieth century.

Anna graduated from South High School in 1913 and from Radcliffe College, Class of 1917, magna cum laude. In 1955 she received a Master’s degree in Education from Clark University. During her second year at Radcliffe she was one of only fourteen sophomores in the top tier of honor students. According to the Boston Globe, a Radcliffe honors student had to have “Very high academic distinction and concurrent testimony in her favor from a sufficient number of instructors.” In 1916, while at Radcliffe, she was elected to Phi Beta Kappa.

After Radcliffe, she taught for a year in Newton and then, for two years, in Millbury. In January 1921 she came to Classical, where she taught English until her retirement in 1966, which was also the year Classical High School closed. For several years she also was head of the English Department of the City’s schools.

In the words of one Classical graduate, she “was an inspirational teacher.” Indeed, less than five years after her arrival, the Class of 1925 would dedicate its yearbook to “Anna C. Shaughnessy, a brilliant scholar, a thorough teacher, and a true and sympathetic friend.” The accompanying photograph shows a young woman of serious mien with haunting, brooding, almost sad eyes.

Anna Shaughnessy labored for the City of Worcester for decades. And yet who (beyond co-workers, close friends, and family—and the many young people whose lives she must have touched) has ever heard of her? Granted, she once did receive a key to the City for her work with young people, which served as her only public recognition. She has been swallowed up in undeserved oblivion.

It is high time Worcester further recognized this dedicated, “inspiring” teacher, for through her long teaching career she would bring honor and credit to the city, not only directly, through her labors with young people, but also indirectly, through the triumphs of her students—at least three of whom rose to become well known writers. And who could possibly calculate her citywide influence during her years as head of the City schools’ English Department?

Three writers that we know about were Stanley J. Kunitz (1905–2006, Classical 1922), Charles J. Olson (1910–1969, Classical 1928), and Milton Meltzer (1915–2009, Classical 1932).

Stanley Kunitz/Photo by Cheryl Richards

Stanley Kunitz was a self-starter if ever there was one. He seems to have chosen the vocation of poet from the start, which does not seem to have been the case with Charles Olson. In his Junior year at Classical, Kunitz was assistant editor of the new student literary magazine, The Argus, and held that post until his Senior year, when he became editor-in-chief. He was a prolific writer for The Argus and a top scholar. Kunitz graduated summa cum laude from Harvard in 1926 and went on to earn a Master’s there as well.

Kunitz would serve two terms as Consultant on Poetry to the Library of Congress—in effect, as Poet Laureate—and one term as actual Poet Laureate of the United States, after that post had been created. According to the critic Robert Campbell, Kunitz became “perhaps the most distinguished living American poet.”

Charles Olson was an outstanding student in all subjects. In his senior year Olson placed third in a national oratorical contest, winning a ten-week tour of Europe. From Classical he went first to Wesleyan University and then, after receiving a Master’s degree there, to Harvard, though he did not finish.

Unlike Kunitz, it took Olson some time to settle on his métier. Not especially interested in poetry during his high school years, once he did settle on it he excelled and is today considered one of the twentieth century’s most important American poets.

THE BOARD OF ARGUS, CLASSICAL HIGH SCHOOL’S LITERARY MAGAZINE, 1927-1928. OLSON IS CENTER BACK/CHARLES OLSON RESEARCH COLLECTION, SERIES: PHOTOGRAPHS, BOX 322, ARCHIVES AND SPECIAL COLLECTIONS AT THE THOMAS J. DODD RESEARCH CENTER, UNIVERSITY OF CONNECTICUT LIBRARIES. USED WITH PERMISSION

CHARLES OLSON/ COPYRIGHT 2015 ELSA DORFMAN/ALL RIGHTS RESERVED/ COURTESY COLOTTECOFBOSTON

In 1969 Olson wrote to Anna Shaughnessy, by then retired from teaching. “My dear Anna S,” he began, continuing somewhat incoherently, “You shldn’t at all be surprised I’ve carried you as close to my heart as the first days I ever sat in your class.”

Milton Meltzer entered Classical in 1928, graduating in 1932. He died in New York City in 2009. A prolific writer, he wrote more than 100 books on such subjects as Jewish, African–American, and American history, primarily for young people.

milton meltzer

Few of the teachers at Classical were interested in ideas, he felt, but simply wanted students to memorize facts, dates, and names. One notable exception was Anna C. Shaughnessy. In his charming little reminiscence of Worcester, Starting from Home, Meltzer notes that it was she who introduced him to Thoreau, one of his favorite authors: he would later write a biography of Thoreau, edit a collection of Thoreau’s political essays, and collaborate on another book about Thoreau.

Years later, during a difficult period in Meltzer’s life, he turned to Thoreau’s Walden. for comfort, coming across this passage:

Every one has heard the story . . . of a strong and beautiful bug which came out of the dry leaf of an old table . . , hatched perchance by the heat of an urn. Who does not feel his faith in a resurrection and immortality strengthened by hearing of this? Who knows what beautiful and winged life, whose egg has been buried for ages under many concentric layers of woodenness in the dead dry life of society, . . . may unexpectedly come forth from amidst society’s most trivial and handselled furniture, to enjoy its summer life at last!’

Upon reading these lines, Meltzer wrote, he began to sob. “The image of a bug emerging into life after all those years in its wooden tomb, touched something deep in me. The tears poured out in relief. Feelings that had been frozen so long, melted in a rush. My wife, who had come running at the sound of crying, looked at me in amazement, then put her arms around me. I felt like one reborn. . . .”

And so it was that Anna Camilla Shaughnessy, a brilliant Irish–Catholic girl from little Cherry Valley, Massachusetts, would help these fledgling writers soar.

***

Postscript: Nicholas Gage on Anna Shaughnessy

NICHOLAS GAGE/PHOTO BY MARI SEDER

Miss Shaughnessy was a superb teacher who gave life and feeling to every piece of writing she taught her students. As I recall, she rarely showed any emotion in dealing with those students, but when she encountered ones with an ability to write, she would spend extra time with them to show them how to make an image in a poem more vivid, a character in a short story more alive, an essay more illuminating. She pushed me to try writing poetry for the only time in my life, and led me to reading classical Greek authors like Plutarch and Thucydides, who became models for me in my writing later.

She would invite the most promising students to join the staff of the school journal, the Argus, which she supervised, and she would use the extra time that afforded her with the students to help them further develop their writing skills. In 1957 she appointed me co-editor of the Argus along with Karen Cotzin—an assignment that would create a foundation for a 40-year journalistic career that included the Worcester Evening Gazette, the Associated Press, the Boston Herald Traveler, the Wall Street Journal and The New York Times.

Miss Shaughnessy was a woman of considerable reserve but students never seemed to mind it because they knew if she praised your work, it was for the work itself, and that gave you the confidence to believe in your own abilities and to strive to improve them. She knew not only how to teach but also how to mentor.