0

0

1

918

5234

WPI

43

12

6140

14.0

Normal

0

false

false

false

EN-US

JA

X-NONE

/* Style Definitions */

table.MsoNormalTable

{mso-style-name:”Table Normal”;

mso-tstyle-rowband-size:0;

mso-tstyle-colband-size:0;

mso-style-noshow:yes;

mso-style-priority:99;

mso-style-parent:””;

mso-padding-alt:0in 5.4pt 0in 5.4pt;

mso-para-margin:0in;

mso-para-margin-bottom:.0001pt;

mso-pagination:widow-orphan;

font-size:12.0pt;

font-family:”Berling Antiqua”;}

By Warren Singh

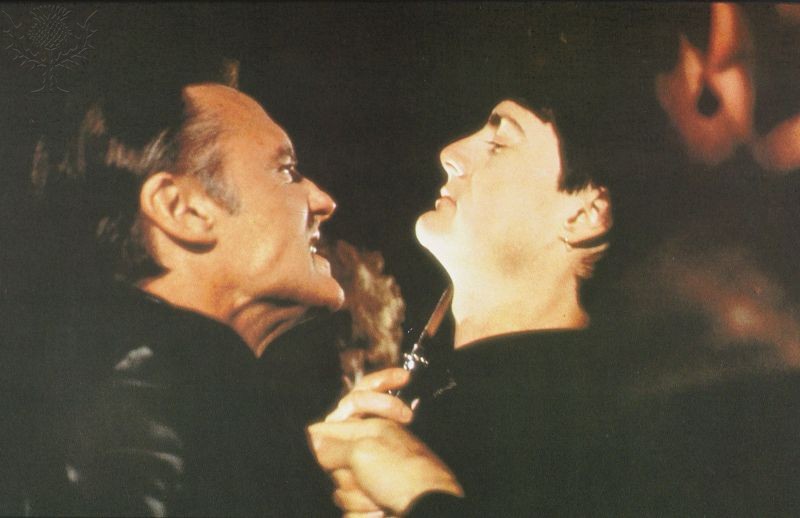

Shane Carruth and Amy Seimetz in Upstream Color / Shane Carruth

It’s complicated.

I think.

Maybe the most incomprehensible thing about Shane Carruth’s film Upstream Color is that it is, in fact, comprehensible.

Perhaps.

My previous experience with Carruth was with his 2004 film, Primer, which was a polished gem of a time travel movie that refused to dumb anything down for the sake of comprehensibility.

Upstream Color opens with Kris, a woman played by Amy Seimetz, who is drugged with a substance from a forcibly ingested roundworm that induces extreme psychological malleability. The assailant then essentially hypnotizes her into emptying her bank accounts and makes off with all of her assets. But this isn’t really about Thief (no really, in the credits he’s simply Thief). The theft really only sets the stage for the rest of the film.

A year later, Kris meets Jeff, played by writer/director Carruth, and they fall in love. But the movie isn’t all about boy-meets-girl, secrets revealed, happily ever after, either. That’s certainly a large element in the movie, but also significant is the role of the parasite itself. It’s never fully explained, but we do know that the life cycle consists of the following: a man known as Keeper (actually credited as Sampler) extracts the roundworm from the victim, and then transplants it into one of the pigs he keeps on a pig farm. Any offspring from the pigs are placed in a burlap sack and thrown into a nearby river. The decomposing bodies then release an unnamed compound that is absorbed by a white flower downstream, which then turns blue. The flowers are collected and sold – and it is the blue color that indicates that the drug-secreting worms are present in the potting soil (this is where Thief gets the worms that he uses on the victims).

Still with me? From pig to plant to human to pig: this is the lifecycle of the parasite, and it’s this cycle that unites all of the characters.

So is the movie about unification? Not quite. Sampler is able see out of the eyes of victims through a connection they have with the pigs whose parasites they ingested, and we see their lives after the fact (they are dramatically different, as job loss and financial ruin frequently follow from Thief’s actions).

It’s about connection, then? Closer. One critical view has been that it’s about identity: how it forms, fractures, and then is rebuilt.

To me, the movie is about trauma. Thief at the beginning of the movie victimizes both Kris and Jeff, even though we see only Kris’ experience. After a time skip, we see the two meet and get to know each other. The effects of the trauma are evident on Kris: when the two get coffee, she pulls out her pills and places the bottles on the table, flatly stating, “this is to save us time.” We’re left to conjecture that she’s on the medication due to the financial, emotional, and professional impact of the drug. She now works an entry-level job at a printing and signage shop, a huge step down from the corporate position she held before.

Jeff isn’t fazed, however, and continues to pursue her. Jeff has also suffered similarly, becoming a pariah in his workplace. And so the outcast and the damsel in depression become a team.

These events are also reflected in the lives of their pigs: the two pigs that correspond to Jeff and Kris are found by Sampler to have paired off at the farm, and eventually have a litter of piglets.

When Sampler drowns this litter, Kris runs out of her workplace on the verge of tears, punching through a window as she leaves. Jeff becomes angry, drops a box of papers, and sprints for the exit, bowling over two coworkers on the way.

They find their way to each other, and make their way home. Running inside, buffeted by emotional forces that neither can explain, they crawl into the bathtub, where, surrounded by emergency supplies, in a room lit by flashlight, they hold each other and wait for the storm to pass.

Upstream Color follows the characters after they suffer at the hands of Thief and become part of the life cycle of the parasite, and the movie then shows the aftermath: the tenuous regaining of equilibrium, the aftershocks, the slow recovery, and finally, the taking back of control at the end of the film through the only real plot ‘twist’ (it’s more of a shake-up) in the movie. The importance of the reclamation of agency is explicitly stated (or as close to explicit as the movie ever gets) when Kris warns Jeff before going out with him, “It’s not my fault when things go wrong.” Jeff tellingly replies, “Yes it is.”

As a sensory experience, Upstream Color is distinct from most mainstream movies, although perhaps that owes more to its belonging to the ‘independent’ category (it premiered at the Sundance Film Festival in 2013) with a color palette that makes for a slow moving, evocative journey that is complemented by the ambient soundtrack. Carruth himself composed the music for the film, and it’s perhaps due to his involvement in every major aspect of the movie that it feels so deliberate: it’s not a frou-frou flapping about, but a constructed, defined piece of cinema with a purpose.

Sometimes with Carruth (OK, most times) that purpose is hard to grasp. Carruth isn’t one to spoon-feed the viewer, and this is a demanding film.

Upstream Color is absolutely worth watching. It’s a complex film that defies quick explanation, rife with alternative approaches to direction, narrative, writing, and sound. It’s a film that many of my acquaintances (and yours too, I suspect) would dismiss as too art-house. It’s definitely a film that is on the outer side of the artistic envelope. It’s also a film that I’m still mulling over close to a year after watching it for the first time.

So go do me a favor and watch Upstream Color. And after you’ve finished, come find me and tell me what you thought the movie was about (no seriously; I’ll buy you a cup of coffee). Because I think it’s complicated.

Upstream Color can be bought and downloaded here.

Warren Singh is a bookworm and wiseacre who sometimes goes undercover as a writer. He also occasionally pretends to be studying chemical engineering at Worcester Polytechnic Institute, Worcester, Mass. Sinecures, paeans, and disproportionately massive bribes may be proffered at probablystillsomewhatincorrect.wordpress.com

;