by Jeremy Levine

The Madding Crowd/550 Music

The Madding Crowd/550 Music

Eva Maldonado

I do not shudder to think of the legion that may have been conceived in your unisex bathrooms, nor of the heart-wrenching breakups that occurred over a plate of hash browns and eggs, nor of the lonely forgettable dinners consumed at the bar by equally lonely truck drivers.

For if you are anything, Waffle House, you are real.

Contrary to movies and sappy novels, people do in fact fail you in the wee hours of the night when you need them the most. Yet never have your greasy door handles been locked, never has the exhausted waitress ignored the request for “just one menu, please.”

Most restaurants are built upon pretenses, niceties, conventions of society. Close your menu when you’re ready to order. Napkins on your lap. Fifteen percent tip. Waffle House is but a satire of these prisons. You are here for food, not for the slimy floors and flickering fluorescent lights and the sad, dull eyes of the barely-eighteen girl in the blue shirt and black apron. And reasonable food is what you will get, at a reasonable price, in a reasonable time.

When the 3 a.m. highway is lit only by the headlights of other soulless, sleep-driven passengers, when you wake up too early and remember that you are the only one that can Krazy-Glue your broken pieces together again, when you’re bored on a Friday night with the only people that have ever made you feel whole—turn not to flashing neon lights, but to those eleven trustworthy tiles of gold.

Dedication to Anna C. Shaugnessy from the Classical High School yearbook of 1966.

Stanley Kunitz/Photo by Cheryl Richards

THE BOARD OF ARGUS, CLASSICAL HIGH SCHOOL’S LITERARY MAGAZINE, 1927-1928. OLSON IS CENTER BACK/CHARLES OLSON RESEARCH COLLECTION, SERIES: PHOTOGRAPHS, BOX 322, ARCHIVES AND SPECIAL COLLECTIONS AT THE THOMAS J. DODD RESEARCH CENTER, UNIVERSITY OF CONNECTICUT LIBRARIES. USED WITH PERMISSION

CHARLES OLSON/ COPYRIGHT 2015 ELSA DORFMAN/ALL RIGHTS RESERVED/ COURTESY COLOTTECOFBOSTON

milton meltzer

***

Postscript: Nicholas Gage on Anna Shaughnessy

NICHOLAS GAGE/PHOTO BY MARI SEDER

The author with a group of Afghani children/photo by jason Boulay

Charlie Rubin and Jacob Beranger/Photo by Dan Leventhal

Erik Abramson with Yan Perez/Photo by Michael Abramson

by Orfa Torres Fermín

A wordcloud based on this article. Design by worditout.com

While in line at the post office a few months ago, I witnessed a man eavesdropping on a Latina chatting with a female companion.

“Speak English,” he said. “You’re not in Mexico.”

The woman, seemingly ashamed, looked at her friend, lowered her voice and head, and continued to speak.

She wasn’t speaking to him.

She wasn’t even speaking Spanish.

I came to the United States of America, my adoptive motherland, when I was in 4th grade. At ten years old, I effortlessly spoke, wrote, read, and sang in Spanish. Soon after enrolling in the Worcester (Massachusetts) Public School system I was placed in ESL classes. I was extremely excited at the prospect of learning English and all that it entailed. I did my best to learn the language. I read English books at home and watched Full House, Punky Brewster, and The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air in the belief that the more English TV I watched and the more English literature I read, the sooner I would learn English. A year and a half later, I was transitioned into English-only classes. There, I was constantly reminded of my accent and the importance of getting rid of it. I was placed in speech classes in order to work on my pronunciation. I worked hard to try to domesticate my unruly tongue.

My inability to master English pronunciation led me to the conclusion that there was something wrong with me. I am now an adult and continue to have an accent—a prominent and untamable one at that. While I proudly remain fluent in Spanish, I now also manipulate the English language with pride. I think in both languages. I find that I am able to better rationalize watching and listening to the news in English but favor reading the newspaper in Spanish. I write better in English yet speak better in Spanish. As a consequence, much of my cognitive exchanges are spent filtering words from English to Spanish or vice versa.

I have met many people, who, like the younger me, feel the need to suppress their Spanish language and accents. They battle with their use of what linguists call code-switching (as well as language, code-switching also involves switching between gestures, social interaction, and culture). You are probably familiar with code-switching as Spanglish. The Spanish-speakers attempting to juggle two languages understand that in order to fit in they need to, like many before them, assimilate to the new language. Many of them walk around feeling the way I did as a child, that there is something wrong with them, a wrongness that is obvious the moment they open their mouths to speak.

By the end of this century, the Latino community will comprise the biggest minority group in the United States. By that time, since the use of Spanish is seldom encouraged, English, and not Spanish will be the mother tongue of most Latinos. This notion creates a problem for Latinos who are caught between two cultures and deal with the complexities of living between two languages on a daily basis.

Language plays a fundamental role in a person’s sense of self. Culture, which includes language, forms our beliefs and shapes our perception of reality. Culture allows people to understand their surroundings and communicate; as with language, culture helps the community transmit the philosophies dear to them.

Code-switching is an aptitude, yet it is profoundly discriminated against, most often by those who speak only one language. The Latino use of code-switching in the United States is a cultural performance deeply frowned upon. For the Latina writer, though, the use of code-switching is a necessity, a tool through which she is able to achieve autonomy. In literature, code-switching is recognized as a literary technique that allows for the alternation between two or more languages in the same text. It can be found in all forms of literature, and it is the natural result of the constant growth in the Hispanic population from the early nineteenth century through to today.

Although it can be argued that the use of code-switching in written text is a political statement against the monolithic use of English—this may be what the man in the line at the post office was worried about—it can also be argued that those who code-switch do it because it is part of their identity, a marker. Code-switching is a representation of the reality of those who live in a liminal state, not only between vernaculars, but also between cultures.

According to Lev Vygotsky, a psychologist who pioneered research into cognitive development, “Language … is the tool of culture which enables social interaction, and thus the direction of behavior and attitudes.” Since culture plays an essential role in the cognitive development of a person, the language in which an individual communicates should not to be regarded as an insignificant.

Code-switching is shows the ambiguities of one who stands in an uncomfortable territory, a place of contradictions, illegitimacy, and manipulation. Code-switching is a language born out of boundaries. It is a mode of communication indispensable to achieving self-efficacy and subsequently self-expression.

Identity and belonging are crucial to the development of human beings. People who have a strong sense of their identity understand and accept where they come from–their cultural history, language, religion, and the environment that helped shape them. People achieve a sense of belonging when their culture is accepted rather than questioned, suppressed or judged.

Code-switching, in this sense, is more than a personal choice. It defines a person and allows him or her to achieve completeness. The failure to fully understand the immigrant experience, the reasons that drive people to leave their countries of birth and journey to the United States, their drives, beliefs, and what shapes them, is what keeps many from understanding that people who code-switch do not do so as a simple rejection of the English language or to keep monolinguals out, but rather because code-switching is the language that the newer generations have come to know as natural.

Orfa Torres Fermin is a Worcester resident and Clark University English and business student. She enjoys researching and writing about women and gender studies, cultural theory, and social and cultural marginalization. She is a self-confessed coffee aficionado, do-it-yourself(er), and photographer. Orfa believes in equality and hopes to live by her pen.

Photo by nick porcella

photo by nick porcella

by Sarah Leidhold

Three women By pablo Picasso, Pablo/State Hermitage / Culture Images / Universal Images Group/all Rights Managed

0

0

1

250

1429

WPI

11

3

1676

14.0

Normal

0

false

false

false

EN-US

JA

X-NONE

/* Style Definitions */

table.MsoNormalTable

{mso-style-name:”Table Normal”;

mso-tstyle-rowband-size:0;

mso-tstyle-colband-size:0;

mso-style-noshow:yes;

mso-style-priority:99;

mso-style-parent:””;

mso-padding-alt:0in 5.4pt 0in 5.4pt;

mso-para-margin:0in;

mso-para-margin-bottom:.0001pt;

mso-pagination:widow-orphan;

font-size:12.0pt;

font-family:Cambria;

mso-ascii-font-family:Cambria;

mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin;

mso-hansi-font-family:Cambria;

mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin;}

Globally, one in three women will be raped, beaten, coerced into sex or otherwise abused in her lifetime.

-From a report by UNIFEM, the women’s fund at the United Nations.

Walk like the wolverine

awaiting attack–

grasp your cold metal keys

like a weapon

in case the bones behind

your knuckles aren’t strong

enough to crack the skull

that’s holding the brain

that’s hatching the plan

to hurt you.

You must be ready.

One in three—

you,

her,

or me.

Restrain your provoking

siren self.

They are easily stimulated.

Every night is

their mating season.

Float just above

the pavement, silent.

Travel in packs;

drape your skirts just

below the come-hither

curves of your ankles.

They can detect fear

in their knowing nostrils–

listen for the crinkle of recognition

and the howl of pursuit.

Slink through the shadows

but avoid the darkness.

Slip ninja stars

into your bra cups

and spray yourself

with skunk musk

instead of perfume.

One in three—

you

her,

or me.

Sarah Leidhold, an overzealous student at Worcester State University, harbors a pervasive addiction to both producing and absorbing poetry. She especially enjoys the uninhibited spilling out of inspired sentiments in the all-accepting form of free verse. More of her work can be found here.

Photo credit: http://quest.eb.com/search/525_2913015/1/525_2913015/cite

“Prismatic Pop”/Mixed Media (Pastel, Colored Pencil, Watercolor, Marker, & Glitter)

INFOGRAPHICS LIKE THIS ONE, WHICH CHARTS WHICH U.S. REGIONS PHISH HAS VISITED ON EACH OF ITS TOURS, ARE COMMONPLACE ON PHISH.NET’S BLOG. IMAGE COURTESY OF PHISH.NET/THE MOCKINGBIRD FOUNDATION.

0

0

1

918

5234

WPI

43

12

6140

14.0

Normal

0

false

false

false

EN-US

JA

X-NONE

/* Style Definitions */

table.MsoNormalTable

{mso-style-name:”Table Normal”;

mso-tstyle-rowband-size:0;

mso-tstyle-colband-size:0;

mso-style-noshow:yes;

mso-style-priority:99;

mso-style-parent:””;

mso-padding-alt:0in 5.4pt 0in 5.4pt;

mso-para-margin:0in;

mso-para-margin-bottom:.0001pt;

mso-pagination:widow-orphan;

font-size:12.0pt;

font-family:”Berling Antiqua”;}

By Warren Singh

Shane Carruth and Amy Seimetz in Upstream Color / Shane Carruth

It’s complicated.

I think.

Maybe the most incomprehensible thing about Shane Carruth’s film Upstream Color is that it is, in fact, comprehensible.

Perhaps.

My previous experience with Carruth was with his 2004 film, Primer, which was a polished gem of a time travel movie that refused to dumb anything down for the sake of comprehensibility.

Upstream Color opens with Kris, a woman played by Amy Seimetz, who is drugged with a substance from a forcibly ingested roundworm that induces extreme psychological malleability. The assailant then essentially hypnotizes her into emptying her bank accounts and makes off with all of her assets. But this isn’t really about Thief (no really, in the credits he’s simply Thief). The theft really only sets the stage for the rest of the film.

A year later, Kris meets Jeff, played by writer/director Carruth, and they fall in love. But the movie isn’t all about boy-meets-girl, secrets revealed, happily ever after, either. That’s certainly a large element in the movie, but also significant is the role of the parasite itself. It’s never fully explained, but we do know that the life cycle consists of the following: a man known as Keeper (actually credited as Sampler) extracts the roundworm from the victim, and then transplants it into one of the pigs he keeps on a pig farm. Any offspring from the pigs are placed in a burlap sack and thrown into a nearby river. The decomposing bodies then release an unnamed compound that is absorbed by a white flower downstream, which then turns blue. The flowers are collected and sold – and it is the blue color that indicates that the drug-secreting worms are present in the potting soil (this is where Thief gets the worms that he uses on the victims).

Still with me? From pig to plant to human to pig: this is the lifecycle of the parasite, and it’s this cycle that unites all of the characters.

So is the movie about unification? Not quite. Sampler is able see out of the eyes of victims through a connection they have with the pigs whose parasites they ingested, and we see their lives after the fact (they are dramatically different, as job loss and financial ruin frequently follow from Thief’s actions).

It’s about connection, then? Closer. One critical view has been that it’s about identity: how it forms, fractures, and then is rebuilt.

To me, the movie is about trauma. Thief at the beginning of the movie victimizes both Kris and Jeff, even though we see only Kris’ experience. After a time skip, we see the two meet and get to know each other. The effects of the trauma are evident on Kris: when the two get coffee, she pulls out her pills and places the bottles on the table, flatly stating, “this is to save us time.” We’re left to conjecture that she’s on the medication due to the financial, emotional, and professional impact of the drug. She now works an entry-level job at a printing and signage shop, a huge step down from the corporate position she held before.

Jeff isn’t fazed, however, and continues to pursue her. Jeff has also suffered similarly, becoming a pariah in his workplace. And so the outcast and the damsel in depression become a team.

These events are also reflected in the lives of their pigs: the two pigs that correspond to Jeff and Kris are found by Sampler to have paired off at the farm, and eventually have a litter of piglets.

When Sampler drowns this litter, Kris runs out of her workplace on the verge of tears, punching through a window as she leaves. Jeff becomes angry, drops a box of papers, and sprints for the exit, bowling over two coworkers on the way.

They find their way to each other, and make their way home. Running inside, buffeted by emotional forces that neither can explain, they crawl into the bathtub, where, surrounded by emergency supplies, in a room lit by flashlight, they hold each other and wait for the storm to pass.

Upstream Color follows the characters after they suffer at the hands of Thief and become part of the life cycle of the parasite, and the movie then shows the aftermath: the tenuous regaining of equilibrium, the aftershocks, the slow recovery, and finally, the taking back of control at the end of the film through the only real plot ‘twist’ (it’s more of a shake-up) in the movie. The importance of the reclamation of agency is explicitly stated (or as close to explicit as the movie ever gets) when Kris warns Jeff before going out with him, “It’s not my fault when things go wrong.” Jeff tellingly replies, “Yes it is.”

As a sensory experience, Upstream Color is distinct from most mainstream movies, although perhaps that owes more to its belonging to the ‘independent’ category (it premiered at the Sundance Film Festival in 2013) with a color palette that makes for a slow moving, evocative journey that is complemented by the ambient soundtrack. Carruth himself composed the music for the film, and it’s perhaps due to his involvement in every major aspect of the movie that it feels so deliberate: it’s not a frou-frou flapping about, but a constructed, defined piece of cinema with a purpose.

Sometimes with Carruth (OK, most times) that purpose is hard to grasp. Carruth isn’t one to spoon-feed the viewer, and this is a demanding film.

Upstream Color is absolutely worth watching. It’s a complex film that defies quick explanation, rife with alternative approaches to direction, narrative, writing, and sound. It’s a film that many of my acquaintances (and yours too, I suspect) would dismiss as too art-house. It’s definitely a film that is on the outer side of the artistic envelope. It’s also a film that I’m still mulling over close to a year after watching it for the first time.

So go do me a favor and watch Upstream Color. And after you’ve finished, come find me and tell me what you thought the movie was about (no seriously; I’ll buy you a cup of coffee). Because I think it’s complicated.

Upstream Color can be bought and downloaded here.

Warren Singh is a bookworm and wiseacre who sometimes goes undercover as a writer. He also occasionally pretends to be studying chemical engineering at Worcester Polytechnic Institute, Worcester, Mass. Sinecures, paeans, and disproportionately massive bribes may be proffered at probablystillsomewhatincorrect.wordpress.com

;

0

0

1

362

2069

WPI

17

4

2427

14.0

Normal

0

false

false

false

EN-US

JA

X-NONE

/* Style Definitions */

table.MsoNormalTable

{mso-style-name:”Table Normal”;

mso-tstyle-rowband-size:0;

mso-tstyle-colband-size:0;

mso-style-noshow:yes;

mso-style-priority:99;

mso-style-parent:””;

mso-padding-alt:0in 5.4pt 0in 5.4pt;

mso-para-margin:0in;

mso-para-margin-bottom:.0001pt;

mso-pagination:widow-orphan;

font-size:12.0pt;

font-family:”Berling Antiqua”;}

by Warren Singh

Decision time, and the fate of the free world hangs in the balance: it’s 1939, and I’ve been put in charge of a new top-secret government project called The Manhattan Project, devoted to developing a game-changing weapon in competition with the Nazis. Given the circumstances, it’s a little nerve-wracking to consider the first thing that I have to do, which is choose a second-in-command to lead the team of physicists that will be the heart and soul of the endeavor.

I’m on page 18 of The Right Decision, an immensely fun read, despite being written like a textbook (which, being published by McGraw Hill, is probably intentional) regarding how to make decisions.

Written by a math professor named James Stein, the book draws from the fields of mathematics and economics (more specifically, decision and game theory) to address better ways of weighing and choosing options. Its chapters are divided into various broad topics: the first part of the book covers an idea central to decision theory, the ‘payoff factor’. Really, it’s a fancy way of saying, ‘what is it that you want out of this?’ Subsequent chapters deal with various ways of assessing the core idea, such as the inadmissibility option (if an option is inferior to other, similar ones, drop it like it’s on fire) or the Bayes criterion (which choice works out best on average?).

Midway, the book takes a pleasantly diverting turn, the reasons for which Stein explains at the beginning. He writes that one doesn’t learn to ride a bike solely by reading about it: you instead take a few core ideas, and then go and practice them until it clicks. Then you vary the situation and do it again. This is what he aims to do with the book, and this is where the fun is. Interspersed through the chapters are problems presented for the reader, in which Stein presents a real or hypothetical scenario and asks what you, the reader, would do. Spanning such diverse scenarios as “my best friend and his girl are having trouble and have broken up, when can I make a move for her” to “in what direction should you take your multinational corporation at this critical juncture,” these problems are immensely entertaining.

The author writes that he hopes that doing these puzzles will be just as entertaining as crosswords or Sudoku, but with the added benefit of helping us make decisions. Stein offers 28 scenarios, complete with solutions. He advises tackling one a day for a month, with the hope that at the end of it, the reader will have vastly improved decision-making skills.

Stein argues that we are the sum of our decisions, his point being that our decisions won’t always lead to good things, as the real world frequently has factors that we can’t influence, but over the long haul good decisions tend to add up better than bad ones.

It reminded me of a championship poker player, who wrote that poker is a discrete game: that is, all the odds are known. If all the odds are known by everyone at the table, then what separates champions from the merely adequate? Well, as he explains, even though the probabilities in poker are well defined, it is possible to make the correct play (there’s always a correct play, given that the probabilities are limited) and lose. A champion player is someone who can make the right play five times in a row, lose five times in a row, and the sixth time, still make the correct play.

The Right Decision doesn’t pretend to deal a winning hand, much less guarantee a good payoff. But it does teach one how to assess the odds, which is oddly liberating. In the end, there are no guarantees, and all we can do is play a beautiful game.

0

0

1

69

395

WPI

3

1

463

14.0

Normal

0

false

false

false

EN-US

JA

X-NONE

/* Style Definitions */

table.MsoNormalTable

{mso-style-name:”Table Normal”;

mso-tstyle-rowband-size:0;

mso-tstyle-colband-size:0;

mso-style-noshow:yes;

mso-style-priority:99;

mso-style-parent:””;

mso-padding-alt:0in 5.4pt 0in 5.4pt;

mso-para-margin:0in;

mso-para-margin-bottom:.0001pt;

mso-pagination:widow-orphan;

font-size:12.0pt;

font-family:Cambria;

mso-ascii-font-family:Cambria;

mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin;

mso-hansi-font-family:Cambria;

mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin;}

0

0

1

69

395

WPI

3

1

463

14.0

Normal

0

false

false

false

EN-US

JA

X-NONE

/* Style Definitions */

table.MsoNormalTable

{mso-style-name:”Table Normal”;

mso-tstyle-rowband-size:0;

mso-tstyle-colband-size:0;

mso-style-noshow:yes;

mso-style-priority:99;

mso-style-parent:””;

mso-padding-alt:0in 5.4pt 0in 5.4pt;

mso-para-margin:0in;

mso-para-margin-bottom:.0001pt;

mso-pagination:widow-orphan;

font-size:12.0pt;

font-family:Cambria;

mso-ascii-font-family:Cambria;

mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin;

mso-hansi-font-family:Cambria;

mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin;}

Warren Singh is a bookworm and wiseacre who sometimes goes undercover as a writer. He also occasionally pretends to be studying chemical engineering at Worcester Polytechnic Institute, Worcester, Mass. Sinecures, paeans, and disproportionately massive bribes may be proffered at probablystillsomewhatincorrect.wordpress.com

0

0

1

686

3916

WPI

32

9

4593

14.0

Normal

0

false

false

false

EN-US

JA

X-NONE

/* Style Definitions */

table.MsoNormalTable

{mso-style-name:”Table Normal”;

mso-tstyle-rowband-size:0;

mso-tstyle-colband-size:0;

mso-style-noshow:yes;

mso-style-priority:99;

mso-style-parent:””;

mso-padding-alt:0in 5.4pt 0in 5.4pt;

mso-para-margin-top:0in;

mso-para-margin-right:0in;

mso-para-margin-bottom:8.0pt;

mso-para-margin-left:0in;

line-height:107%;

mso-pagination:widow-orphan;

font-size:11.0pt;

font-family:Calibri;

mso-ascii-font-family:Calibri;

mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin;

mso-hansi-font-family:Calibri;

mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin;}

by Abby Frias

As a niña, the smells of rice, beans, and plantains seeping beneath my grandparents’ door were so strong that I believed they possessed magic. Like fairy dust, the perfume would billow through the cracks and spread down the retirement home’s hallway, putting every other apartment under my grandparents’ velvety Dominican spell.

Today, as a high school junior, I find my grandmother’s cooking no less enchanting. I ascend in the building’s elevator, and anxiety weighs heavier with each passing floor. I mentally prep my brain for rapid translations, verb conjugations, topics of conversation, until — Ding. The elevator doors open and an immediate plume of warmth melts my nervousness.

I stand and read the bronzed numbers on the last door on the right. 455. Quatrocientos

0

0

1

2

16

WPI

1

1

17

14.0

Normal

0

false

false

false

EN-US

JA

X-NONE

/* Style Definitions */

table.MsoNormalTable

{mso-style-name:”Table Normal”;

mso-tstyle-rowband-size:0;

mso-tstyle-colband-size:0;

mso-style-noshow:yes;

mso-style-priority:99;

mso-style-parent:””;

mso-padding-alt:0in 5.4pt 0in 5.4pt;

mso-para-margin:0in;

mso-para-margin-bottom:.0001pt;

mso-pagination:widow-orphan;

font-size:12.0pt;

font-family:Cambria;

mso-ascii-font-family:Cambria;

mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin;

mso-hansi-font-family:Cambria;

mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin;}

cincuenta y cinco? My Spanish is not what it should be. I knock.The door opens and my grandfather beams at me.

“¡Hola chica! ¿Como estás?”

“¡Hola abuelo!” These words I know, having used the greeting countless times over the years. I feel safe and relaxed in my grandfather’s strong embrace.

“Abigalita.” From behind, a different, gentler voice. Mi abuelita. I turn and smile into the deep glimmer in her wise eyes–ponds sparkling under moonlight. Her wrinkles swell and recede as she smiles up at me. A brown, weathered canvas of strength, each line and etched tale of strength, joy and, of course, grief. My father’s passing undoubtedly left emotional and physical scarring. I have had several years to mourn and cope with the loss, but each visit is a reminder of all of the possible conversations between my grandparents and I that never happen because of my rudimentary Spanish skills.

***

0

0

1

72

416

WPI

3

1

487

14.0

Normal

0

false

false

false

EN-US

JA

X-NONE

/* Style Definitions */

table.MsoNormalTable

{mso-style-name:”Table Normal”;

mso-tstyle-rowband-size:0;

mso-tstyle-colband-size:0;

mso-style-noshow:yes;

mso-style-priority:99;

mso-style-parent:””;

mso-padding-alt:0in 5.4pt 0in 5.4pt;

mso-para-margin:0in;

mso-para-margin-bottom:.0001pt;

mso-pagination:widow-orphan;

font-size:12.0pt;

font-family:Cambria;

mso-ascii-font-family:Cambria;

mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin;

mso-hansi-font-family:Cambria;

mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin;}

In the 1970’s, my grandparents emigrated from the Dominican Republic with their four sons. They worked in New York City, diligently crafting a better future for their family and unborn generations. But the land of opportunity came at a price. By the time their grandchildren came along, both my abuela and abuelo were far too oriented to their native tongue. We were free to enjoy each other’s food and company; however, my grandparents’ and I lacked the foundation of a shared language.

They did not give up, however. I remember at the age of five joining them at their English classes and “assisting” the teacher each day. My grandfather learned to string together phrases in the strange, new language, but my grandmother had a harder time. Thus, I’ve learned to read the “context clues”– body language, facial expressions, and hand gestures– to decipher her meanings.

“Abigailita, ¿Quieres comer?” My grandmother motions to the dining room table and pulls out a chair.

The table is filled with pastelitos, yuca, beans and other delicious dishes. The three of us join hands, my clammy fingers and chipped black nail polish against the smooth, cocoa-butter enriched grooves and arches of their palms. I squeeze tightly and lower my head.

They wish me a successful junior year of high school, good health and good grades and that God gives me a long life with joy, happiness, and–a good sweater? Wait, suerte doesn’t mean sweater, it means luck. They ask that God grant us many meals in the future and that God looks after Ramon.

Ramon. It’s my father’s name–his real name, not the Anglicized “Ray” that I heard most often. I repeat it in my head, rolling the “r” and emphasizing the “mon.” I repeat it once more, aloud, and raise my head as a pause of silence blankets our prayer circle. My grandfather’s eyes are brimming with tears. I hug him and smile. We say “Amen.”

***

I am flourishing under the parenting of my Irish-American mother and Italian-American stepfather–two amazing, nurturing, loving parents. Yet when I’m with my grandparents, we three always seem silently aware of the absence of Ramon, Ray, their son, my dad. This absence of a wnoderful man is like a branch broken from our family tree. But between mouthfuls of rice and circles of prayer, I recognize the tree’s undying strength. I feel safe and loved under its shade.

Abby Frias is a student in the Wachusett Regional School District. She hopes to pursue a writing career and study political science in college.

Photo Credit:

Oak Trees in Farm Field. [Photography]. Encyclopædia Britannica ImageQuest. Retrieved 14 Jan 2015, from

http://quest.eb.com/#/search/300_2265907/1/300_2265907/cite

by Sasha Kohan

Punk was defined by an attitude rather than a musical style.

— David Byrne

0

0

1

1412

8050

Boston College

67

18

9444

14.0

Normal

0

false

false

false

EN-US

JA

X-NONE

/* Style Definitions */

table.MsoNormalTable

{mso-style-name:”Table Normal”;

mso-tstyle-rowband-size:0;

mso-tstyle-colband-size:0;

mso-style-noshow:yes;

mso-style-priority:99;

mso-style-parent:””;

mso-padding-alt:0in 5.4pt 0in 5.4pt;

mso-para-margin:0in;

mso-para-margin-bottom:.0001pt;

line-height:115%;

mso-pagination:widow-orphan;

font-size:11.0pt;

mso-bidi-font-size:10.0pt;

font-family:Arial;

color:black;}

To be clear: I am not here to talk about what’s punk and what’s not. As much as I’d like to have the authority to do so, my knowledge of punk is scant compared to what I really love – pop. And while the two may seem to be diametrically opposed, it seems to me that pop is beginning to take a few small but visible notes from punk’s playbook.

Pop culture infiltrates our lives – in fashion, film, slang, TV – trickling through our minds, memories, and conversations in big and small ways, but perhaps most obviously in music. And right now – sorry guys – women own the playing field. The influence these women can have (and are already having) on thousands of girls today could be immense, but what are we actually learning from them? And is it really as bad as some people seem to think?

Exhibit A: Taylor Swift. Undeniably attractive as she may be, the seven-time Grammy winner is also undeniably more conservative than most of her other female pop peers, somehow remaining as innocent and adorable as when she released her debut album in 2006; for all we know, Ms. Swift has been completely sober and sexless for all her twenty five enchanting years on earth. Despite the self-professed confessional nature of her songwriting, criticism of what some may call an obsession with boys continues to crop up year after year. Referred to as “a feminist’s nightmare” by Jezebel, Swift has publicly admitted that her relationships are most often what inspires the strong feelings behind her songs, with countless defenders who thrive on the connection built between the artist and fans in hearing familiar stories and moments retold in such an articulate, relatable voice. What some interpret to be a “feminist’s nightmare” is Swift’s apparent inability to write about anything but these relationships, with haters arguing that the lyrical message of her music is little more than simply, BOYS; fans, however, see something very different.

Lana del rey performing at the isle of wight festival in 2012 / amir Hussein / Getty Images Entertainment / Getty Images / Universal Images Group

NPR interestingly called Swift a “princess of punk” upon the release of her fourth album, Red, in 2012, commenting on the noticeably new attitude of the songs and noting that Swift’s growth is evident in the tones of both anger and acceptance (as opposed to what might have previously been called whining and obsession) felt throughout the album. Swift’s maturation is by far most visible in light of her newly-released fifth studio album, 1989, and is perhaps most palpable in the single “Blank Space” and its music video. In what the New York Times called a “metanarrative” about her reputation as a perpetually lovelorn, occasionally clingy ex-girlfriend, Swift seems to have directly dedicated “Blank Space” to her haters, shamelessly acknowledging her notoriety in lines like “You look like my next mistake” and the gleefully knowing chorus, “Got a long list of ex-lovers / They’ll tell you I’m insane / But you know I love the players / And you love the game.” The accompanying video brings Swift’s self-awareness to a new level, following a traditional fairy-tale love story and featuring caricatures of Swift’s alternately girl-next-door and crazy-ex personas, teaching us just as much about rolling with the punches and knowing yourself as her earlier songs did with issues of growing up and dealing with young love and heartbreak. Swift is in good company though: fellow pop princess Lana Del Rey also defied the mainstream culture by abandoning the reputation built by hip-hop inspired Born to Die (2012) when packing her second album Ultraviolence (2014) full of slow, psychedelic songs, none of which make the traditional three-minute radio cut. Del Rey took a bow to her skeptics as well, most notably in the Ultraviolence song “Brooklyn Baby,” which highlights haters’ perceptions of the artist whom Rolling Stone called “rock’s saddest, baddest diva” as an unapologetic hipster. Swift may have taken a note from Del Rey’s book as she gave her haters exactly what they were looking for in “Blank Space.” Though Swift’s sugar-sweet, pure-as-a-virgin image may have made (and continues to make) her music marketable to younger listeners and often causes older ones to undermine or disregard her music, Swift is undeniably succeeding in the powerful cultural position she holds – in fact, because her sound is so accessible to young girls, she is actually instilling her ideas of how to work through relationships and expressing strong feelings in girls at a younger age – kind of empowering, right? And isn’t that the kind of ability we’d like our daughters growing up with?

The one girl who probably has the most to say on growing up is actually the youngest of most pop stars on the radar right now. At 16, Lorde topped the U.S. Billboard Charts in 2013 with her hit “Royals,” from her debut album, Pure Heroine (the name itself basically says all you need to know). Now, at 18 years old, Lorde remains admirable in a traditional sense — incredibly talented, wildly successful — yet at the same time “punk” in the way she defies our expectations; a 16-year-old girl writes an album almost entirely absent of boys, romance, or sex? Her incredibly impressive debut instead focused mainly on the concept of youth and the strangeness of getting older, a theme as universal as Ms. Swift’s obsession with writing about boys. “Royals” even challenges the elements of songs on the radio as of late: “But every song’s like gold teeth, Grey Goose, trippin’ in the bathroom / blood stains, ball gowns, trashin’ the hotel room / we don’t care.” How punk is it to write a number one international hit song that rolls its eyes at every other number one hit?

And then there’s Miley. Once the woman of the hour, arguably old news, yet consistently relevant and discussed amongst fans and cynics alike.

Ridding herself of the long, luscious, Hannah Montana locks in favor of a Twiggy-inspired shaved head and bleach blonde bangs, and crowned as “Princess of Twerk” by tabloids everywhere.. Cyrus has gone through an incredible transformation. Under intense public scrutiny for the majority of her life, the singer received shocking amounts of negative publicity in the aftermath of the controversial 2013 VMA performance. Her public sexuality and discussion of drug use has been criticized as an overly dramatic way of saying, “Y’all check me out, I’m not a kid anymore,” and her carefree attitude towards the situation has upset parents telling CNN they are now forced to think that Cyrus does not either a) care what her younger fans think of her or b) hasn’t even bothered to think of what her actions are doing to her image…but isn’t that what continues to make her so awesome?

miley cyrus performing in london

Despite the scandal created around her new look, Cyrus is flourishing more than ever because she simply does not care – which is why VICE magazine even went so far as to call her “the most punk rock musician around” at the height of her controversy. Subsequent appearances on Saturday Night Live and The Ellen Show proved her capacity for eloquence, honesty, and a good sense of humor (about herself) and what it’s like to suddenly be the most talked-about person in the world. She’s not perfect, but she’s rich, pretty, and testing her limits, paving the way for her own independent image, trying to figure out who she is.

That Cyrus can disguise her fourth album, Bangerz, (which is, in fact, a breakup album) as what most angelheaded hipsters would write off as another shitty pop record trying too hard to get in the Top 40 is actually an incredible feat. When some girls might be tempted to fill their album with acoustic emotion and bittersweet strings, Cyrus shook off her broken engagement with actor Liam Hemsworth by reestablishing her confidence in herself: “So don’t you worry ‘bout me, Imma be okay / Imma do my thang.” The lyrics of the album tell the story of real feelings, but the upbeat quality of most of the songs instills a sense of conviction and empowerment – occasionally admitting to unhappiness, but never giving in to it. “Wrecking Ball” is the obvious exception, but we can allow her a few minutes of sadness, right? And can we please allow her to wear what she wants? To dance how she wants? Though the initial hysteria surrounding the transformation of Ms. Cyrus has faded, I think it’s important to remember how harshly and cynically many of us reacted. Everyone has (had) at least a little bit of Miley in us, in our reckless, fun, experimental youth. We watched her evolve and now here she is, and some people still want to criticize her for not keeping things PG? All I can say is: grow up.

Rock critic Lester Bangs said that “punk represents a fundamental and age-old Utopian dream: that if you give people the license to be as outrageous as they want in absolutely any fashion they can dream up, they’ll be creative about it, and do something good besides.” Not to say that girls like Miley, Taylor Swift, Lana Del Rey, and Lorde are punk musicians — not at all — but they’re bringing an element of the tradition into mainstream popular music. The women of pop are stronger than ever as they continue to top the charts, make bank, and make the news every week, joining the ranks of Beyoncé, Lady Gaga, and other established queens of the radio. As they use their words, sounds, and images to express themselves with confidence and be who they choose to be, listeners of our generation should feel more and more comfortable following suit. Punk is, after all, “just another word for freedom.”

Editor’s Note: An earlier version of this article appeared in the magazine STIR in 2013.

Sasha Kohan is a student at Clark University, Worcester, Mass., studying English and Screen Studies.

Photo credits:

5th Annual ACM Honors – Red Carpet. [Photography]. Encyclopædia Britannica ImageQuest. Retrieved 14 Jan 2015, from

http://quest.eb.com/#/search/115_3897402/1/115_3897402/cite

Isle of Wight Festival – Day 2. [Photography]. Encyclopædia Britannica ImageQuest. Retrieved 21 Jan 2015, from

http://quest.eb.com/#/search/115_3972752/1/115_3972752/cite

Capital FM’s Jingle Bell Ball – Day One – Show – London. [Photography]. Encyclopædia Britannica ImageQuest. Retrieved 14 Jan 2015, from

0

0

1

935

5331

WPI

44

12

6254

14.0

Normal

0

false

false

false

EN-US

JA

X-NONE

/* Style Definitions */

table.MsoNormalTable

{mso-style-name:”Table Normal”;

mso-tstyle-rowband-size:0;

mso-tstyle-colband-size:0;

mso-style-noshow:yes;

mso-style-priority:99;

mso-style-parent:””;

mso-padding-alt:0in 5.4pt 0in 5.4pt;

mso-para-margin-top:0in;

mso-para-margin-right:0in;

mso-para-margin-bottom:8.0pt;

mso-para-margin-left:0in;

line-height:107%;

mso-pagination:widow-orphan;

font-size:11.0pt;

font-family:Calibri;

mso-ascii-font-family:Calibri;

mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin;

mso-hansi-font-family:Calibri;

mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin;}

by Alexandra D’Ordine

DOCTOR WHO (Peter Capaldi) and clara oswald (Jenna Coleman) in the tardis / BBC

Walk into any sci-fi convention like Comic-Con and you’re bound to find a few people dressed as metal-encased Daleks and hear the buzzing of a sonic screwdriver. You may even run into attendees wearing bowties or curiously striped scarves and shouting “Allons-y!” If these elements don’t ring a bell, you’re most likely part of the ever-decreasing population of Americans who are unfamiliar with the British television show and cultural phenomenon, Doctor Who.

After celebrating its 51st anniversary last year, Doctor Who is as popular as ever. Throughout its long history, the premise has remained the same: an alien time-traveler, a Time Lord called the Doctor, scoops up various companions and shows them the universe via his living time machine, a blue police box called the T.A.R.D.I.S, which stands for Time and Relative Dimension in Space (a police box is an obsolete telephone callbox for use by the police). Every so often, the Doctor regenerates, meaning his body and personality changes in response to a deadly force. This plot line and the constant replacement of the Doctor’s companions have allowed the show to continue more than half a century.

The show has had its ups and downs in the U.K., including the series’ cancellation in 1989 and a 1996 film version that received a lukewarm response. However, the revived series that began in 2005 has returned the show to its former popularity and more.

Alan Kistler, author of Doctor Who: A History, is familiar with how the show has changed over the years.

“In the revival series, I think the first two years were a major high point, redefining the show and stripping the mythology of Doctor Who back to basics–a strange and mysterious alien on his own who wanted to explore the impossible,” said Kistler. “By 2005, you also had the BBC now adopting what had been successful in the U.S. in making science fiction shows more mainstream.”

The show was not completely new to the U.S. Some of the pre-2005 episodes were shown on PBS, but they didn’t catch on. SyFy offered the revived series but was unable to achieve the necessary audience. Then, in 2009, BBC America started airing current episodes at roughly the same time as they were broadcast in the U.K. It was a success. The premiere of the fifth series in 2010 had 1.2 million viewers, according to The Hollywood Reporter, which at the time was a record for any show on BBC America.

“BBC America started a stronger U.S. advertising campaign starting with season 6, so that’s definitely pushed its popularity further,” said Kistler.

Three years later, the 50th anniversary special was shown in 94 countries on six continents, achieving the Guinness World Record for the largest simulcast of a TV drama. Many of these viewers were in the U.S., one of the few countries in which the special was also shown in theaters.

Since last year it has become even more popular, with the premiere of the eighth series on August 23, 2014 attracting 2.58 million viewers, making it the highest rated premiere ever on BBC America, according to TV By the Numbers.

Glenn Grothaus is a Doctor Who enthusiast from St. Louis, Missouri, who started watching the show in 2010 and has been a fan, or “Whovian,” ever since. Last summer he attended the St. Louis Comic-Con and was pleased to meet Matt Smith, the actor who played the Eleventh Doctor.

“I had heard about Doctor Who but was under the misperception that it was some weird British sci-fi show,” said Grothaus. “But I liked the idea of them [the Doctor and his assistants] wanting to do good.”

The show began to catch on here with people such as Grothaus for a multitude of additional reasons. For example, some recent episodes have been set in the U.S. and a native of Scotland with an American accent, John Barrowman, was cast as recurring supporting character, Jack Harkness. Several episodes were also filmed in the U.S., such as one that takes place in Manhattan.

“There’s no set genre or interpretation, so people can take what they wish from the show,” said Kistler.

Peter Capaldi and Jenna Coleman on the Empire State Building / BBC

Also, the Internet and social media have been instrumental in the show’s globalization.

“Streaming services have allowed Americans to catch up on the new show very easily,” said Kistler. “Before, fans might have been the only person in their class or workplace to like Doctor Who. Now, even if that’s the case, Twitter and Tumblr are full of online communities that encourage each other to watch and discuss more of the show.”

“I actually went to the St. Louis Science Center for a Doctor Who night,” Grothaus said. This included speakers, exhibits, and showings of several episodes. “They never would have had that 10 years ago. But it’s global now.”

At Comic-Con, Grothaus saw Matt Smith’s panel and the demand for Doctor Who right in the middle of the country.

“[Matt Smith] said he was amazed by how the popularity here has exploded in the past several years,” Grothaus said.

Grothaus said that the Comic-Con panel also included fans that had been unusually moved by the show, including a young girl struggling with mental illness who said that Doctor Who showed her the importance of hope and perseverance.

So there you have it—Doctor Who can even heal.

“It disguises it[self] as sci-fi,” Grothaus said, “but it’s so much more.”

Grothaus also observed that the show’s themes of equality and social justice seemed to appeal to many younger Americans.

However, this successful expansion of the franchise is not without dissent: some fans of the classic series do not approve of its globalization and feel that it has lost its characteristic British tone. Amanda Keats of Yahoo TV: U.K. & Ireland cites the Eleventh Doctor’s memorable wearing of a Stetson hat and the inclusion of characters that are CIA agents.

Some long-time fans that Grothaus saw at Comic-Con may have shared this view, but he noted that they were generally accepting of new fans.

“They were totally encouraging the younger fans to jump in,” he said.

Grothaus is an elementary school teacher and sees first-hand how Doctor Who appeals to children. “It speaks to all ages,” he said. “It’s universal in its themes of loyalty, adventure, bravery, and sacrifice. And when you have that, you can reach anyone, no matter what age, gender, or race.”

Alexandra D’Ordine is majoring in Biochemistry and Professional Writing at Worcester Polytechnic Institute, Worcester, Mass. She enjoys writing about anything from popular culture to science, playing piano (particularly Chopin), and learning as much as possible.

Normal

0

false

false

false

EN-US

X-NONE

X-NONE

/* Style Definitions */

table.MsoNormalTable

{mso-style-name:”Table Normal”;

mso-tstyle-rowband-size:0;

mso-tstyle-colband-size:0;

mso-style-noshow:yes;

mso-style-priority:99;

mso-style-parent:””;

mso-padding-alt:0in 5.4pt 0in 5.4pt;

mso-para-margin-top:0in;

mso-para-margin-right:0in;

mso-para-margin-bottom:8.0pt;

mso-para-margin-left:0in;

line-height:107%;

mso-pagination:widow-orphan;

font-size:11.0pt;

font-family:”Calibri”,sans-serif;

mso-ascii-font-family:Calibri;

mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin;

mso-hansi-font-family:Calibri;

mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin;}

.

0

0

1

63

364

WPI

3

1

426

14.0

Normal

0

false

false

false

EN-US

JA

X-NONE

/* Style Definitions */

table.MsoNormalTable

{mso-style-name:”Table Normal”;

mso-tstyle-rowband-size:0;

mso-tstyle-colband-size:0;

mso-style-noshow:yes;

mso-style-priority:99;

mso-style-parent:””;

mso-padding-alt:0in 5.4pt 0in 5.4pt;

mso-para-margin-top:0in;

mso-para-margin-right:0in;

mso-para-margin-bottom:auto;

mso-para-margin-left:0in;

text-align:justify;

mso-pagination:widow-orphan;

font-size:12.0pt;

mso-bidi-font-size:11.0pt;

font-family:”Times New Roman”;

mso-bidi-font-family:”Times New Roman”;

mso-bidi-theme-font:minor-bidi;}

by Gloria Cadder

it’s not quite ice that stops

plants from flowering

though they still

grow for years

ice preserves roadkill

on yellow two-way lines

lampless, lit by moonlight

nothing will thaw

the ice by spring—unless a body

will ignite, release

the blooming bones

Vanitas by Scott Holloway / photo by scott holloway

0

0

1

24

141

WPI

1

1

164

14.0

Normal

0

false

false

false

EN-US

JA

X-NONE

/* Style Definitions */

table.MsoNormalTable

{mso-style-name:”Table Normal”;

mso-tstyle-rowband-size:0;

mso-tstyle-colband-size:0;

mso-style-noshow:yes;

mso-style-priority:99;

mso-style-parent:””;

mso-padding-alt:0in 5.4pt 0in 5.4pt;

mso-para-margin:0in;

mso-para-margin-bottom:.0001pt;

mso-pagination:widow-orphan;

font-size:12.0pt;

font-family:Cambria;

mso-ascii-font-family:Cambria;

mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin;

mso-hansi-font-family:Cambria;

mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin;}

Gloria Cadder is a senior at Brandeis University in Waltham, Mass. Her work has appeared in Tethered by Letters, Laurel Moon, Where the Children Play, and the Brandeis Law Journal. See more of her work at morethanamovie.com.

0

0

1

966

5509

WPI

45

12

6463

14.0

Normal

0

false

false

false

EN-US

JA

X-NONE

/* Style Definitions */

table.MsoNormalTable

{mso-style-name:”Table Normal”;

mso-tstyle-rowband-size:0;

mso-tstyle-colband-size:0;

mso-style-noshow:yes;

mso-style-priority:99;

mso-style-parent:””;

mso-padding-alt:0in 5.4pt 0in 5.4pt;

mso-para-margin-top:0in;

mso-para-margin-right:0in;

mso-para-margin-bottom:8.0pt;

mso-para-margin-left:0in;

line-height:107%;

mso-pagination:widow-orphan;

font-size:11.0pt;

font-family:Calibri;

mso-ascii-font-family:Calibri;

mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin;

mso-hansi-font-family:Calibri;

mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin;}

by Sasha Kohan

Well, I did it: I finally forced myself to watch some of the “classics” I’ve somehow missed on my inadvertent journey to becoming a Screen Studies major. By compiling a list of every movie I am ashamed to have never seen and forcing my friends to initial the ones they wouldn’t mind watching twice, I figured I had set myself up for success, achievement, culture, education. I chose Easy Rider (1969, Dennis Hopper), The Birds (1963, Alfred Hitchcock), and Blue Velvet (1986, David Lynch).

hitchcock with avian friend during the making of “The birds,” 1963

And now, here I am, trying to consider exactly what I’ve seen.

I’ve seen a lot of things.

I’ve seen a man with bloodstained holes where his eyes used to be, another gruesomely stabbed to death in a sleeping blanket, and a group of gangsters moved to tears by a lip-synched rendition of “In Dreams.” More unsettling, I’ve seen Dennis Hopper as both one half of a freedom-chasing, drug-using motorcycle duo and as a sadomasochistic sociopath who gets off wearing a gas mask. Perhaps even more unsettling still, I’ve seen a vulnerable Jack Nicholson (vulnerable? Jack Nicholson?) succumb to the peer pressure of two freewheeling hippies and anxiously take a hit of his first joint.

Needless to say, these movies have left me with a lot on my mind, while 20 years of life and education have left me with an infuriatingly insufficient ability to articulate it all. I’ve nearly finished the course requirements that fulfill my Screen Studies major thus far, and as a result I can critically examine the meaning of certain camera angles, costume decisions, light temperature, and transitions, among other details. I could point out the total absence of non-diegetic music in the soundtrack of The Birds, how horribly the silences enhance the anticipation of impending crowing sounds, how starkly it contrasts with the feel-good road trip playlist of Easy Rider and the recurring nominal theme of Blue Velvet. I could analyze Hopper’s jarring quick cuts back and forth from present to future, scene to scene, and explain how such an unconventional technique underlines how strange the easygoing motorcycle life seemed to the square society surrounding Billy and the aptly and unsubtly named Captain America. And I could talk about how Blue Velvet – well, I wouldn’t even know where to start.

But this is the trouble when movie lovers become film students. Once you are trained in the art of noticing technicalities, the ability to simply sit back and watch a movie slowly but surely evolves into a constant process of interpretation and evaluation, until you suddenly find yourself reading an impossible amount into every romantic comedy and action movie you see with your family, and they all get sick of you asking what they thought because “I liked it” is no longer good enough. Frankly, and from a film student’s unrelenting eye, the movies I watched are so rich with deliberate mysteries, I feel I could write a thesis for each one in an attempt to solve it all – but there is a thin thread tying together my discombobulated train of thoughts. Hanging over my mental rubble is a hazy but discernible smog, an overwhelming and conflicted sense of America.

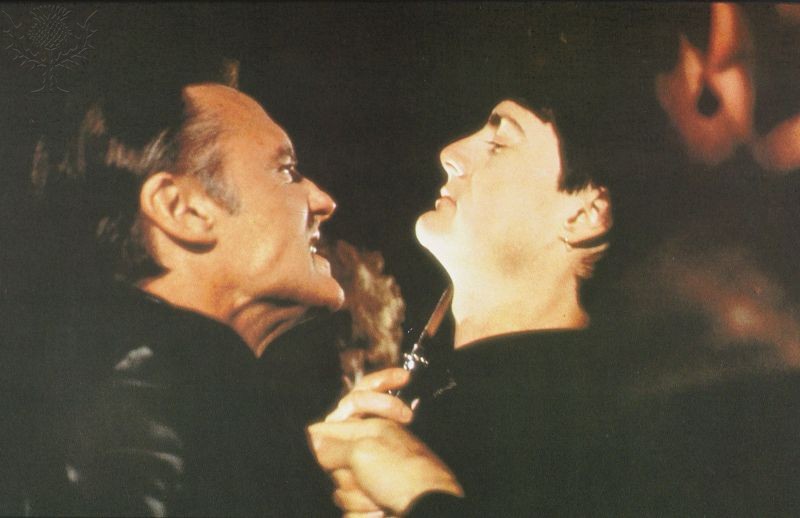

Dennis hopper charms kyle maclachlan

But what else is new, really? On-screen, off-screen – the Americas are the same.

Though these films are aesthetically dated in ways that could never be recreated now without accusations of insincerity or that unconvincing, too-smooth Hollywood glow, I was surprised (I don’t know why) to realize that, in theory, America is just as terrifying as it always has been. Whether I imagined the past or the present as more of a golden age I couldn’t say; I have just always been under the impression that something fundamental had changed between “now” and “then,” but now, I’m not so sure. A while back, I recall posting a rare politically-charged status on Facebook regarding the Supreme Court decision which allows corporations to refuse contraception health coverage, openly wondering how we’ve allowed things to get so unreasonably out of control. (I try to keep these comments few and far between – sooner or later, everyone starts to hate that one person who posts too much of a too-strong opinion). Through my passionately confused, concerned fit of outrage, dulled only by the silent, padded walls of the Internet, I was suddenly reminded of Easy Rider’s tagline: “A man went looking for America. And couldn’t find it anywhere.” Then an image of Blue Velvet struck me, vaguely – white picket fence, green grass, red roses, and all the filth that lives beneath.

dennis hopper and peter fonda in “easy rider”

America. Looking. Can’t find. Anywhere.

It was all so big, I wasn’t sure if the links were truly there or if I had imagined them in a desperate attempt to create some meaning in my stupid life – and then – Godzilla! The Birds! Apocalypse! America! It was there, all there! It was all one horrible, beautiful web of fiction and lies, of myth and reality, of now and then, of me and of them.

What really unites The Birds, Blue Velvet, and Easy Rider, is the responsibility of the individual, and the deeply significant absence of love. Whether or not this is indicative of some universal lack of love for the American Dream is relevant in some ways, but irrelevant in others. Human relationships, whether between Tippi Hedren and her handsome pet store customer, Blue Velvet‘s young hero and his high school lover, or Billy and Captain America, are irrelevant to these stories. While flirtation, sex, and friendship do exist and move the plot, the utter emptiness of these relationships mainly highlight the utter emptiness of these characters and the world they live in – that is to say, America. Things have changed – the specifics, yes (the distinctly eighties hair, the sixties cinematography, the political context, the popular culture) – but what struck a nerve in me was realizing how true these movies still are, and how alone we and you and I often feel in the universal longing to do or make something worthwhile, in this world or in ourselves, asking, is this the way to live?

Perhaps, as it so often happens, I’m reading too much into things. Perhaps I’m a twenty-something cynic, doomed to a life of reading Dostoevsky with troubled, furrowed brows. Or perhaps I ought to buy a pack of cigarettes and Mrs. Wagner’s pies, walk off, and look for something better than the America found here.

Sasha Kohan is a student at Clark University, Worcester, Mass., pursuing a degree in English and Screen Studies.

Photo Credits:

Alfred Hitchcock. [Photography]. Encyclopædia Britannica ImageQuest. Retrieved 14 Jan 2015, from

http://quest.eb.com/#/search/158_2481394/1/158_2481394/cite

BLUE VELVET (1986) – HOPPER, DENNIS; MacLACHLAN, KYLE. [Photography]. Encyclopædia Britannica ImageQuest. Retrieved 14 Jan 2015, from

http://quest.eb.com/#/search/144_1534583/1/144_1534583/cite

EASY RIDER (1969) – HOPPER, DENNIS; FONDA, PETER. [Photography]. Encyclopædia Britannica ImageQuest. Retrieved 14 Jan 2015, from

http://quest.eb.com/#/search/144_1555235/1/144_1555235/cite

0

0

1

124

709

WPI

5

1

832

14.0

Normal

0

false

false

false

EN-US

JA

X-NONE

/* Style Definitions */

table.MsoNormalTable

{mso-style-name:”Table Normal”;

mso-tstyle-rowband-size:0;

mso-tstyle-colband-size:0;

mso-style-noshow:yes;

mso-style-priority:99;

mso-style-parent:””;

mso-padding-alt:0in 5.4pt 0in 5.4pt;

mso-para-margin-top:0in;

mso-para-margin-right:0in;

mso-para-margin-bottom:10.0pt;

mso-para-margin-left:0in;

line-height:115%;

mso-pagination:widow-orphan;

font-size:11.0pt;

font-family:Calibri;

mso-ascii-font-family:Calibri;

mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin;

mso-hansi-font-family:Calibri;

mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin;}

by Dylan Dodd

ernest hemingway’s high school yearbook photo, 1917 / encyclopaedia britannica imagequest

Your eyes, they show it.

The expression is synthetic.

Raised brow, awkward grin.

Your usual half-smile that

Only shines to the left is not

Proper. Hands folded, one

On the other, no

Bent fingers or spaces between,

Pressed stiffly on a block

With a less than clever “B,”

Made for infants (and picture day.)

You twist your head until

It strains your neck, chin up.

chin up.

This is how people want

To see you, hair solid

With spray, wearing a shirt

That you will never wear again—

Molded clay in a metal chair.

Wait for the click. Relax.

Dylan Dodd studies English at Worcester State University and loves nature, the arts, and the way life works. More of his work my be found at www.dylantdodd.wordpress.com.

by Sam Hark

0

0

1

218

1247

WPI

10

2

1463

14.0

Normal

0

false

false

false

EN-US

JA

X-NONE

/* Style Definitions */

table.MsoNormalTable

{mso-style-name:”Table Normal”;

mso-tstyle-rowband-size:0;

mso-tstyle-colband-size:0;

mso-style-noshow:yes;

mso-style-priority:99;

mso-style-parent:””;

mso-padding-alt:0in 5.4pt 0in 5.4pt;

mso-para-margin:0in;

mso-para-margin-bottom:.0001pt;

mso-pagination:widow-orphan;

font-size:12.0pt;

font-family:Cambria;

mso-ascii-font-family:Cambria;

mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin;

mso-hansi-font-family:Cambria;

mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin;}

0

0

1

218

1247

WPI

10

2

1463

14.0

Normal

0

false

false

false

EN-US

JA

X-NONE

/* Style Definitions */

table.MsoNormalTable

{mso-style-name:”Table Normal”;

mso-tstyle-rowband-size:0;

mso-tstyle-colband-size:0;

mso-style-noshow:yes;

mso-style-priority:99;

mso-style-parent:””;

mso-padding-alt:0in 5.4pt 0in 5.4pt;

mso-para-margin:0in;

mso-para-margin-bottom:.0001pt;

mso-pagination:widow-orphan;

font-size:12.0pt;

font-family:Cambria;

mso-ascii-font-family:Cambria;

mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin;

mso-hansi-font-family:Cambria;

mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin;}

Railway Track In The Early Morning Mist / encyclopaedia britannica imagequest

Sam Hark

Goddamnit. It’s now 6 past 7. Trains like dirty tin-can caterpillars

slog inandout of this hollow cocoon of South Street Station.

In front of me a raw flurry of existence flutters by, all glory & madness.

Above me, the footsteps of rain begin their fevered dance, jittering free upon

a slant glass ceiling. Beside me, Sully sits furrowed, lost between the soggy

flaps of an outdated TV Guide (seemingly the last one in existence).

Which (most likely) prompted the existential query that caused his

eyes to bloom like the dusty wings of a moth as he prodded:

if ya could, wouldja’ wanna even know the time of your death?

& on the usual day, one unlike the one I am describing to you here, I would

respond without breath. For I would live out my pre-counted days as the glut King of

Certainty, swilling my red wine from the grandest of goblets like it was rainwater, lazing

upon my gilded throne, gazing with pity upon peasants toiling in muddied fields of

mortality beneath my golden heel. I would tick through this prescription of time as the

sure-sighted surgeon of ephemerality, the true scourge of all obscurity.

But as I previously stated (please see above), this day was unlike the

others that stack higher than an infinite pile of unused TV Guides.

On this day, as the rainwater softly fills my worn boots,

can I come to realize the distinctive grace in the wait for a train

that is all too certain to arrive.

Sam Hark studies English and Philosophy at Assumption College, Worcester, Mass. His influences are John Hodgen, Gregory Corso, Arthur Rimbaud, and Tony Hoagland.

0

0

1

1354

7718

WPI

64

18

9054

14.0

Normal

0

false

false

false

EN-US

JA

X-NONE

/* Style Definitions */

table.MsoNormalTable

{mso-style-name:”Table Normal”;

mso-tstyle-rowband-size:0;

mso-tstyle-colband-size:0;

mso-style-noshow:yes;

mso-style-priority:99;

mso-style-parent:””;

mso-padding-alt:0in 5.4pt 0in 5.4pt;

mso-para-margin:0in;

mso-para-margin-bottom:.0001pt;

mso-pagination:widow-orphan;

font-size:10.0pt;

font-family:”Times New Roman”;

border:none;}

by Kieran Sheldon

Two years ago, yearning to relieve the monotony of a four-day family road trip, I happened upon a novel entitled The Strange Affair of Spring-Heeled Jack by Mark Hodder. According to the synopsis on the back, Sir Richard Burton, Victorian-era explorer and agent of the Queen, was heading into Victorian London’s slums in search of arch-criminal Jack. The synopsis seemed interesting enough, and the cover involved some sort of interesting stilt-walking figure wreathed in blue lightning, so I bought it.

I’d visited London before, and thoroughly enjoyed it. However, real-world London had nothing on Hodder’s version, which was populated not only by the expected lofty lords and cursing cabbies, but also by genetically engineered werewolves, clockwork automatons, and a man who had transplanted his brain into an orangutan. Colossal airships blotted out the sun. Historical figures had been somewhat modified. For instance, in Hodder’s London, Isambard Kingdom Brunel, Victorian-era engineer, survived beyond his presumed death in an enormous steam-powered mech-suit. Somehow, I don’t suspect that the real Brunel accomplished such a feat.

Oh, and as it turns out, Spring-Heeled Jack was a time-traveller.

I had next to no idea what I was reading, but I loved it. Through blind luck, I had stumbled upon steampunk.

Well, consider my monotony relieved.

As a literary genre, steampunk involves the fantastical juxtaposition of the technology and beliefs of the Victorian era with those of today. This anachronism results in such contraptions as clockwork robots and galleons that hover on the aether. Mike Perschon, Professor of English at MacEwan University, proposes on his blog, The Steampunk Scholar that steampunk is characterized by three things: technology powered by dubious or unexplained science, a Victorian-era aesthetic, and an exploration of how the men and women of the past imagined their future. Thus the clockwork robots, and much else.

Steampunk also influences fashion and art. Designers incorporate Victorian garments and airship goggles into their outfits, while artists build modern relics that echo the magnificence of the past. For instance, renowned steampunk craftsman Jake von Slatt modified the pictured guitar by electrolytically etching cogs onto its faceplate.

jake von slatt and his steampunk guitar / jake von slatt

However, when steampunk bleeds beyond the written word and into other cultural phenomena, such as fashion, music, or art, its definition quickly grows less distinct. Primarily, this stems from steampunk’s appeal to those countercultural souls who actively defy definition. Many who incorporate steampunk elements into their artwork do so as a rebellion against popular culture. Therefore, as soon as popular culture begins to understand the steampunk movement, its adherents change its definition.

At first, I was a bit put off by steampunk’s emphasis on rebellion, which had always seemed destructive and ugly to me. However, I came to find steampunk’s take on rebellion fascinating, because it focuses not on destruction, but creation. Steampunk artists, designers, and musicians declare their disdain for some facet of modern culture not by tearing it down but by designing something new and beautiful to take its place. These artists are often referred to simply as “makers,” and for good reason, since they build fantastical devices the likes of which this world has never before seen.

Perhaps most visibly, steampunk rebels against the impersonal nature of modern technology. Many steampunk artists find themselves dismayed by the mass-produced, homogenized gadgets that fill modern markets. Goggles firmly in place, these adventurous souls construct the personalized, artistic technology that they wish was more prevalent in the world. Thomas Willeford, a maker who works mostly in leather, and who built the marvelous ornithopter backpack pictured, points out that “something can be very functional and still have a sense of beauty about it. Where are the wood-grain laptops? Where are the beautifully picture-framed monitors that are commercially available? The monitor is made from induction-molded plastic. It wouldn’t be that much harder to make it look better.”

THOMAS WILLEFORD’S ORNITHOPTER BACKPACK / JESSE WALKER

Steampunk also objects to modern technology’s mechanical incomprehensibility to the average man or woman. In the Victorian era, most technology, involving nothing more than pressurized air and cogs, was understandable without years of specialized study. Williford explained that, instead of presenting iDevices and laptops that seem almost magical in their cryptic operations, “steampunk likes to say, ‘Here’s how our science works. See this steam engine here?'”

The leatherworker bemoans our age’s lack of practical know-how. “I find the inability of people to use tools to be rather abhorrent,” he said. “It is the opposite of being self-sufficient and self-powered. The ability to use tools makes one better prepared for adversity.”

Steampunk suggests a single solution to these many issues: build the type of technology that you want to see in the world, and build it with your own hands. Through this experimentation with technology, often referred to as “tinkering,” steampunk devotees not only make themselves more mechanically knowledgable and capable, but simultaneously create art. Thus, again, the movement eschews the destruction of the unsatisfactory in favor of the creation of something better.

Wearers of steampunk fashion act in a similar manner, casting aside modern dress in favor of top hats, vests, goggles, corsets, and all manner of brass bits and bobs. Styles range from simple hats and vests to such gloriously inconvenient contraptions as Willeford’s ornithopter backpack. Disappointed with the ripped jeans and brand-name sweatshirts of today? Why not wear the sophisticated suits and gowns of yesterday? Some steampunk devotees do just that, while others wear clothing inspired by the practical, utilitarian garb of the Victorian-era worker, the better to hold all of their tinkering tools. Once again, steampunk advocates the creation of a fantastical Victorian-inspired alternative to a less-than-fantastical aspect of modern life.

Mark Eliot Schwabe, a “SteamSmith” / Mark Eliot Schwabe

Mark Eliot Schwabe, a “SteamSmith” who designs intricate metal brooches and charms with airship motifs, contends that steampunk also encourages rebellion through sheer politeness, in an echo of the refined etiquette of the Victorian age. Schwabe notes that one of the reasons he was attracted to steampunk was that when he first encountered it was that, in those days, “our American society was not as well-mannered as it is, actually, now. People were all too frequently in your face. And Victorian manners were a refreshing alternative to that.”

Willeford also objects to modern rudeness, which, he said, is too often passed off as harsh honesty. “Bludgeoning people with ‘honesty’ is rude and, worse, it’s lazy,” he said. “When you take the time to be polite to the people around you, you are telling them that they are worth that time.” In this way, Steampunk combats modern rudeness through imitation of the manners of a more refined age, another of its anachronistic solutions to the less pleasant aspects of modern life.

Not everyone is persuaded of Steampunk’s cultural significance. English professor Mike Perschon, who teaches at MacEwan University in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada, claims that the ethos of steampunk culture has strayed from that of steampunk literature, which does not often incorporate the same countercultural ideals. He also believes that other forms of steampunk do not have the significance that many devotees attribute to them. While studying the genre, he far more often encountered “steampunk that just wanted to tell a ripping good yarn” than steampunk advocating countercultural ideals. In addition, while some members of the steampunk community see steampunk as a statement that “we’re disillusioned with the iPod world we inhabit,” when he has visited steampunk conventions, he has noticed fans toting “a lot of iPods.”

“Steampunk won’t change the world,” he said. “People will.” He alluded to a story Jake von Slatt had shared with him about some steampunk friends of his who volunteered repairing bicycles in Africa. “That’s world-changing,” Perschon said. “But as I understand it, none of them were dressed in goggles or top hats when they did it. “

airship brooch / MARK ELIOT SCHWABE

Maybe steampunk won’t change the world on its own, but it might just point the world in the right direction. After all, making our society more individualized, polite, and self-sufficient certainly qualifies as a noble cause. Certainly, the modern world proves far superior to the Victorian era in many ways, but perhaps the turning of the years has taken something away from us, too. Perhaps too much of our technology and culture has become, in the words of Schwabe the SteamSmith, “same-same.”

“I think many people worldwide have felt the need to individualize and personalize and customize objects and experiences,” Schwabe says, “and steampunk is an excellent vehicle for doing just that.”

0

0

1

50

291

WPI

2

1

340

14.0

Normal

0

false

false

false

EN-US

JA

X-NONE

/* Style Definitions */

table.MsoNormalTable

{mso-style-name:”Table Normal”;

mso-tstyle-rowband-size:0;

mso-tstyle-colband-size:0;

mso-style-noshow:yes;

mso-style-priority:99;

mso-style-parent:””;

mso-padding-alt:0in 5.4pt 0in 5.4pt;

mso-para-margin:0in;

mso-para-margin-bottom:.0001pt;

mso-pagination:widow-orphan;

font-size:12.0pt;

font-family:Cambria;

mso-ascii-font-family:Cambria;

mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin;

mso-hansi-font-family:Cambria;

mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin;}

Kieran Sheldon admits that he is a bit odd. His myriad pastimes include playing nerdy board games, wearing top hats, and growing carnivorous plants. He also writes a good deal of fantasy and science fiction, but never without his trusty pirate squid, Cal, at his side. He is a junior at Bancroft School in Worcester, Massachusetts.

0

0

1

1879

10714

WPI

89

25

12568

14.0

Normal

0

false

false

false

EN-US

JA

X-NONE

/* Style Definitions */

table.MsoNormalTable

{mso-style-name:”Table Normal”;

mso-tstyle-rowband-size:0;

mso-tstyle-colband-size:0;

mso-style-noshow:yes;

mso-style-priority:99;

mso-style-parent:””;

mso-padding-alt:0in 5.4pt 0in 5.4pt;

mso-para-margin:0in;

mso-para-margin-bottom:.0001pt;

line-height:200%;

mso-pagination:widow-orphan;

font-size:12.0pt;

font-family:”Times New Roman”;}

by Nick Porcella

Last summer I decided I would stay in my college town of Worcester, Mass, rather than return home. I picked up a job in Admissions and an internship at the Worcester Art Museum, and, for the first time in my life, I found myself on a nine-to-five, Monday-through-Friday schedule. The weekends were mine. Work ended at 5 p.m. on Friday and did not require my attention until 9 a.m. Monday. No homework. No appointments. I remember that first weekend kicking around my apartment, unsure of what to do with myself.

“Get used to it,” my Dad said, laughing. He’s been doing this for decades.